Over the last couple of years, I’ve probably talked with 500 investors. It’s been a pretty wide range, from professional investors working at family offices or large institutions to lawyers, doctors, and small business owners.

I believe for (almost) all investors, the biggest thing they could do to improve their risk-adjusted returns is not to get better at “picking winners” but to get better at diversification and portfolio construction.

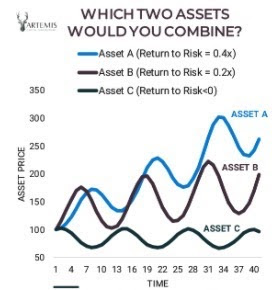

As a simple example, let’s say you have the ability to buy two assets out of a possible three choices.

The first two assets, Asset A and Asset B have higher returns than Asset C but are highly correlated with one another. They track one another and the business cycle. Both do well when markets are up and poorly when markets are down.

The third asset, Asset C, loses money overall. That is, it has a slightly negative return. However, while asset C loses money overall, it goes up in periods where A&B go down. Its most substantial gains are reserved for the periods when the other two assets are in crisis.

If you can only buy one asset, Asset A is the obvious answer.

But, if you can buy two, what is the best overall portfolio?

Obviously, the fact that I am asking it shows it is a trick question.

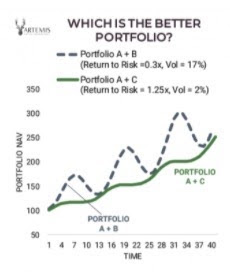

Counterintuitively, the portfolio that combines the negatively correlated (Assets A+C) outperforms dramatically from a risk-adjusted perspective, even though Asset C has a negative yield.

In this example, by combining Assets A and C, which are negatively correlated to each other, when Asset C goes down, Asset A tends to go up, and vice versa.

By combining A+C, you can generate the same long-term returns as A+B with much less risk. This is because of the power of anti-correlation and rebalancing. In periods where A is going up and C is going down, some of the profits from A are being rebalanced into C. This means that when the cycle turns and Asset A starts to go down, Asset C is more “fully funded” such that its gains will come at the best possible time. As A is falling, an investor with this portfolio would be able to buy more of Asset A using the profits from Asset C.

By having anti-correlated assets and rebalancing between them, investors are able to systematically “buy low and sell high.”

In other words, the anti-correlation of C is worth MORE than the excess return to the overall portfolio.

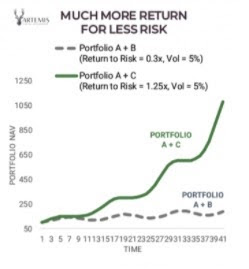

If you want to increase your return, it is safer* to add leverage to the balanced portfolio (Assets A+C) rather than using a portfolio that has correlated risks (Assets A+B).

Most investors don’t do this in practice though. Most investors think purely in terms of the expected value of a single asset. They say “I like this stock and that stock”.

But, diversification math shows that you can combine lower returning individual assets for a higher expected value of the portfolio’s return.

If you like this stock, can you then find something else you might not like as much, but should behave in a negatively correlated way?

This is, of course, a toy model and the real world is not so simple. Portfolio A+C is superior under the assumption that they remain negatively correlated (hence the asterisk after safer). If A&C become correlated, then you can get in trouble.

Even for investors that understand the power of anti-correlation and diversification, I believe they tend to rely too much on historical correlations. We don’t know what the future will look like, but we know it won’t look exactly like the past.

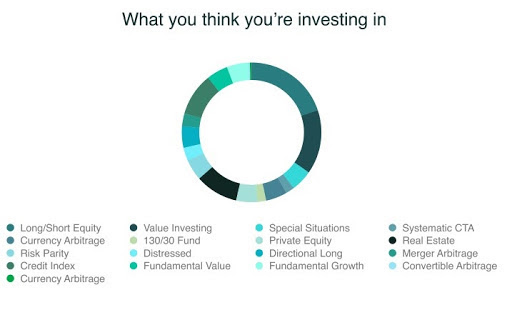

Many investors think they are diversified with a portfolio of domestic stocks, international stocks, some single name stocks they like, some bonds. Maybe they throw in a little bitcoin or angel investing to “barbell” the portfolio.

These types of portfolios seem diversified in good times but when you have a big crash and liquidity dries up, it turns out that you just had 20 barely different flavors of the same “short volatility” trade on.

Short volatility is just another way of saying “risk-on” or “long GDP” – it is a bet on the good times continuing.

March 2020 was a lesson for many investors in this idea. Lots of people who thought they were diversified in January looked at their portfolio at the end of March to see pretty much everything was moving in the same direction.

To get the benefits of diversification that allow you to compound wealth faster, you need something in your portfolio that is long volatility and benefits when markets go risk-off.

I am talking my own book to some extent here as this is what Mutiny Fund is trying to do, but even many sophisticated investors I know don’t understand and implement these two basic facts:

- The returns of a portfolio are “other than the sum of its parts” – combining uncorrelated or anti-correlated assets can improve portfolio-level returns.

- Using assets that are uncorrelated in “good times” but become correlated in a large drawdown does not equal diversification.

Some investors would accept these points and argue that Asset C doesn’t really exist. Though I personally disagree, that’s a fair argument and worth taking seriously. However, most don’t even get to that point and miss the first two essential points!

If you’re interested in diving deeper into this idea, Artemis CIO, Chris Cole, makes this same point using historical data in his paper The Allegory of the Hawk and the Serpent.

Also worth reading up on is Harry Browne’s Permanent Portfolio which implements this in a pretty simple and easy to implement way. The Breaking the Market blog has also done a great job of explaining many of these concepts as well as Resolve Asset Management.

The key takeaways on diversification and portfolio construction:

- Investors should spend less time trying to “pick winners” and focus more on portfolio construction and diversification.

- True diversification requires owning other assets than just stocks and bonds.

All images used in this post are fully credited to Artemis Capital Management.

Last Updated on June 13, 2022 by Taylor Pearson