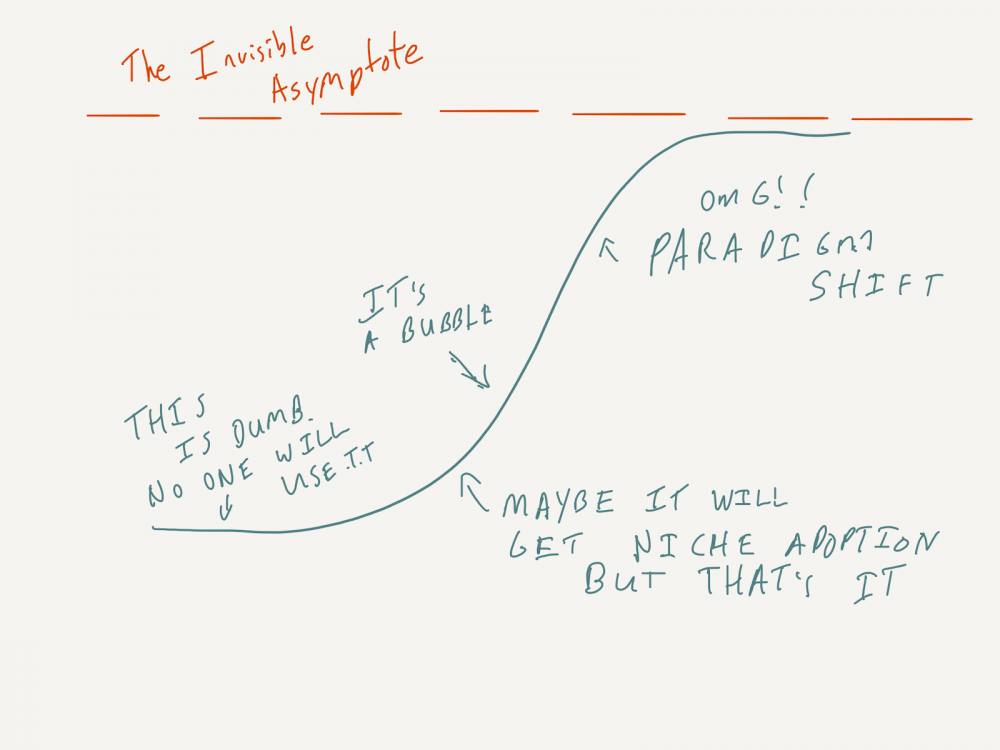

Eugene Wei, an early employee at Amazon, has an excellent blog post on invisible asymptotes. It is worth reading in full, but to briefly summarize, the idea is that as a company grows, it will approach invisible asymptotes where its growth slows in certain areas. This idea is captured in the technological S-Curve:

An otherwise ignored technology or company suddenly gains major traction, becomes ubiquitous, then hits an invisible asymptote and growth slows, though no one saw it coming.

Today’s boring industries were yesterday’s high tech companies – 100 years ago, if you were starting an electricity company then you were working on high technology.

Every successful business goes through the famous S-curve. Almost always, the asymptote of that S-curve is invisible. It’s obvious in retrospect where the S-curve plateaus but not so obvious in the moment. I had dinner with someone last year who sold their AI company in 2012 because they thought we were at the peak of the AI-hype trend. Whoops… It seems silly now, but for someone that had been in the industry for a decade and seen it 10x or 100x from 2002-2012, it didn’t seem so crazy at the time.

The notion of an invisible asymptote is a helpful and powerful framing because once you make the invisible, visible, you can start to deal with it. Indeed Amazon has been astoundingly good at seeing the asymptotes they are approaching and developing new lines of business to continue growing.

There is something else that is often invisible and too often ignored: an invisible absorbing barrier.

An absorbing barrier is a point that you reach beyond which you can’t continue. Being dead is an absorbing barrier. There is a big, big difference between being a little bit alive and being dead. Once you’re dead, you ain’t coming back.

Similarly, there’s a big difference between losing most of your money and losing all of it. You’re either bankrupt or you’re not. For companies, there is a big difference between being a little bit solvent and insolvent. It’s a qualitative, not just quantitative difference.

Some absorbing barriers are obvious: standing in the middle of the interstate or betting your entire life savings on black at the roulette wheel in Vegas. No one is surprised when these sorts of actions end badly.

However, similar to asymptotes, most absorbing barriers are not obvious. They are invisible. We don’t know when we have taken on risk of ruin until it is too late.

Take the example of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM). LTCM was founded in 1994 by John W. Meriwether, the former vice-chairman and head of bond trading at Salomon Brothers. Members of LTCM’s board of directors included Myron S. Scholes and Robert C. Merton (who shared the 1997 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences). Five other MIT Ph.Ds were partners in the firm (three of whom had taught at Harvard Business School). Suffice it to say that the average IQ in their conference room was higher than the heat index on the hottest West Texas day. (For you Celsius people, that’s like 140 farenheit)

LTCM was initially successful with an annualized return of over 21% (after fees) in its first year, 43% in the second year and 41% in the third year. In 1998, it’s fourth year in business, it hit the absorbing barrier, losing $4.6 billion in less than four months.

Implicit in their name Long-Term Capital Management, was the belief that the absorbing barrier was very far away. They expected to be around for a long time.

Narrator: they were wrong.

There was an invisible absorbing barrier a lot closer than they realized.

Many don’t realize you have taken on blow-up risk until it is too late. LTCM crossed an invisible absorbing barrier well before they actually blew up.

Absorbing barriers tend to be invisible to most of us because it is not intuitive to humans psychology that volatility clusters.

As a thought experiment, imagine 100 ladders lined up against a long wall. Each has a 10% probability of falling over.

If the ladders are spaced out and independent from one another, each being used in a different spot, the probability that all of them fall is astronomically low.

There is about a 1020x higher chance of randomly selecting a particular atom out of all of the atoms in the known universe than all the ladders falling down at the same time.

However, if we line all the ladders up next to each other and tie them together, the dynamic is different.

We have made them “safer” in the sense that the likelihood of any individual ladder falling will be much smaller. If one ladder starts to tilt, the weight of all the others will support it.

However, we will have also massively increased the chance that all of the ladders might fall down at the same time.

If one ladder starts to tip, it causes another ladder to tip. That causes the next one. At some point there is a “phase shift” where enough of the ladders have started falling that they will bring down all the others.

In the first scenario, we have lots of moderate volatility. The chance of one ladder falling is pretty high, but we’re unlikely to see all of them fall at the same time.

In the second scenario with all the ladders tied together, we will see alternating periods of very low volatility and very high volatility. Either none of the ladders fall or all of them do.

This is a metaphor for a vast amount of the world we live in.

Though I’m stretching the metaphor a bit, LTCM’s investment strategy was kind of link tying all the ladders together. It seemed to be a brilliant way of reducing volatility and eliminating risk. It turned out that it actually made the absorbing barrier closer, but less obvious.

The interconnectedness of travel routes increases the probability of pandemics such as the Spanish flu and coronavirus and increases the speed at which they spread. Volatility goes from very low to very high.

The interconnectedness of our financial systems results in long periods of stability but then the possibility of massive and violent global market crashes. The interconnectedness means volatility clusters more which causes seemingly distant absorbing barriers to get close too fast to react.

I don’t think it is a coincidence that 2020 has been marked by huge amounts of volatility in not just the virus, but social, economic, and political systems as well. These things are not isolated. They are deeply intertwined. Volatility in one can spill over into another in a negative feedback loop that ends with an absorbing barrier.

This interconnectedness exists in our own lives. One of my pet peeves is when people give investing examples like “If you had bought Amazon stock at its peak in 1999 and held it for 20 years, you would have done great in the long term.”

From 1999, the price of the stock collapsed by over 90%. The type of person that bought a bunch of Amazon stock in 1999 probably also bought a bunch of other crap stocks and had a job in tech. In 2001, they had to sell everything to make rent.

Sure, if they had no volatility anywhere else in their lives, then I guess they could have held the Amazon stock. The problem is that’s not a realistic assumption.

It would have been nice if the only volatility we saw in 2020 was in response to a global pandemic and not economic, political, and social as well, but that’s just not how complex systems tend to function.

As Vladimir Lenin put it “There are decades in which nothing happens and weeks in which decades happen.”

What matters is not average correlation, but correlation during a crisis or black swan event.

If an investor has to eventually reduce his or her exposure because of losses, or margin calls, or because of retirement, or because a loved one got sick and needs an expensive surgery, the investor can discover that an absorbing barrier that seemed far away, is suddenly very close.

What matters is not how large the safety exits are in a theatre on average, what matters is how easy they are to pass through when everyone is running for the door during a fire. (see also: ergodicity)

The key from a financial perspective is to prepare for a situation where the markets drop, your job income gets hit, and you have a personal issue at the same time. In one lifetime, it will likely happen. Volatility tends to cluster.

One common piece of personal finance advice is to set up an emergency fund – keeping 3-12 months of your expenses in cash that you only touch in times of emergency. This is effectively a rule of thumb which increases resilience against an invisible absorbing barrier. While it’s impossible to predict what you might need it for, having it pushes off an absorbing barrier.

In a business context, this might look like diversifying different choke points in your business. If you rely on a single factory to do all your manufacturing, can you get another factory to do 20% of the work even if you pay more per unit just so you have a backup? This seems like a frivolous waste of time when things are going well, but it can be the difference between solvency and insolvency.

Once we acknowledge that there are invisible absorbing barriers, we can start to manage them. If we don’t, then, to riff off Carl Jung, “Until you make the invisible visible, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

Last Updated on October 12, 2020 by Taylor Pearson