What do theories of guerilla warfare, college football, and running a company have to do with the development of modernism and postmodernist philosophy?

Kind of surprisingly, I think the answer is a lot.

Let’s start with football (of the American variety). Generally, the way that the game is played is that there is a head coach along with an offensive and defensive coordinator. Generally, the coordinators are watching the games from the sidelines (or the box) and will call in specific plays to the offense and defense respectively.

These plays are generally “fixed.” That is, every player has a specific role and they would do the same time every time it was called.

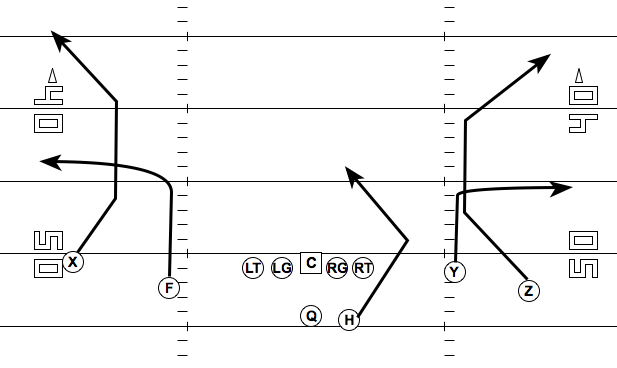

One play might look something like this. When the ball is snapped, the play starts and each of the receivers on the outside (these are the ones that catch the ball) would be told to run a specific route, indicated by the line with an arrow.

So when the play starts, those receivers would all run their routes and the Quarterback (one who throws the ball) would have to choose which receiver to throw it to.

This style of football kind of reminds me of chess. The coordinators are the chess masters and the players are the pieces on the board, each with a specific and circumscribed role.

Over the last ten or twenty years, there’s been a bit of a shift in how the game has been played by some teams. One of the biggest changes is that it is increasingly common for the players to make more of their own decisions on the field

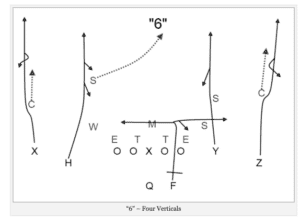

Take this play as an example.

You can see that all the receivers have what are usually called “option routes.” There are multiple arrows branching off of each receiver and the receiver has the option to choose which route they want to run. They are choosing that option based on what the defense is giving them.

This strategy devolves a lot of decision making from the coaches to the players. The players are no longer like chess pieces that only move in one direction, they have a fair amount of autonomy.

The downside to this approach is that it relies on receivers and quarterbacks to “read” the defense the same.

Generally, receivers may have very simple rules of thumbs to determine which route to run. For example, if the defender is playing them close then they may run a long route since they are more likely to be able to beat the defense deep. If the defender is playing far away then they may run a short route since there is more space underneath.

If the quarterback and the receiver get a different read of how the defense is playing, then the quarterback can throw it to the wrong spot and turn it over.

So it’s true that giving this autonomy to the players can be dangerous. A typical football play is about 4 seconds long. There isn’t a lot of time to think through things, you want players to react instinctively and very quickly. When you give more options, you run the risk that they mess it up or are paralyzed by analysis paralysis.

However, if the quarterback and the receiver are in sync and make the same read of the defense, then this approach is incredibly effective. No matter what defensive play that the defensive coordinator calls, the offense can adjust to attack it’s weakness.

If the defense plays back then the offense throws the ball underneath.

If the defense plays up, then the offense throws the ball over the top.

The essential shift here is that decision making is devolved further down the chain of command. When done well, this gives the offense a huge advantage.

It’s like the defensive coordinator can only move his chess pieces in the circumscribed way, but the offensive pieces can go anywhere they want.

If you are playing chess and all your players can move like queens then it’s an enormous advantage. You have a much larger degree of freedom and can beat a much better opponent. I call this The Farthest Down the Chain Principle. You want to push the decision making as far down the chain as is reasonable.

This realization is at the heart of John Boyd’s OODA (Observe, Orient, Decide Act) Loop strategy which studied how insurgent guerilla forces could triumph over large enemies. The Vietnam/American War was much different from the World Wars earlier in the 20th century, in large part because the Vietnamese applied this same technique of devolving decision-making down the chain and as a result were able to fight successfully against a much larger force. Fighting against a good guerilla force is like fighting a many-headed Hydra, cut one head off and two grew back.

By moving the decision making farther down the chain to the players, the offense is able to get inside the OODA loop of the defense. The defensive coordinator can only orient at the time scale of a full play. The offense on the field can orient during the play. They have a tighter OODA loop making it incredibly hard to defend.

This same principle is true in running a company. Startups rely on getting inside the OODA loop of their competitors. If you can observe, orient, decide and act in an hour and BigCo requires a year, that’s a big competitive advantage. Sometimes big enough to unseat massive incumbents.

However, many CEOs and managers try to behave like the offensive coordinators of yesteryear – they want to have complete control over what each of their team members is doing. Often this is an ego thing where they want to “be the boss” though sometimes it is just how people learned to manage.

But you get back in the same scenario here where you are playing chess with pieces that can only move in circumscribed positions. If your competitors are giving more autonomy to the individual contributors, they can react faster.

I think this evolution in strategies across domains is somewhat an outgrowth of how philosophy has evolved over the past century. The traditional approach to football, management and investing could be described in the words of James C. Scott as high modernist.

It rests on the underlying belief that you can just figure out all the inputs and variables and then a smart central planner can come up with the perfect solution. I read this a sort of logical conclusion to Newton and the enlightenment. There was this really empowering idea that started with Newton’s discovery of physical laws that the natural world could be reduced to principles or axioms and then problems could be “solved” deterministically.

And in certain simple problems, this actually does works incredibly well. If you know the speed and direction of a billiard ball on a pool table, then you can calculate where it is going to end up.

The issue you run into is that reality has a surprising amount of detail. You can calculate where one billiard ball will end up, or even two, but as soon as you get to three billiard balls, you have a three-body problem. Unlike two-body problems, no general closed-form solution exists. The resulting system is chaotic and effectively impossible to predict.

Almost every problem we deal with in our lives is way more complicated than just figuring out how three pool balls are going to move.

The logic behind pushing decisions down the chain to the individual closest to the problem is that the person closest to the problems understands the problem and its many details the best. John Boyd referred to this as Fingerspitzengefuhl, a German word that translates to fingertip feeling.

True experts have some level of intuitive or tacit knowledge that may be hard for them to explain (though they should try) which makes them more adept at dealing with that problem.

Fingerspitzengefuhl works in concert with another key principle: Schwerpunkt.

Schwerpunkt literally translates as the center of gravity or emphasis but is best understood as focus or the main priority.

In military terms, it is usually the geographic point of attack.

In business terms, it is having a clear focus and empowering your team to make decisions for themselves in an uncertain environment.

There are lots of ways to do this, but it generally looks something like quarterly goals, having a mission statement, and referencing guiding principles in your calls.

The Farthest Down the Chain Principle means always asking the question “What is the farthest down the chain that I can push this decision?”

You want to maximize the autonomy of people. This also has the nice benefit that you tend to attract the best people. The best people believe they are good and they want more control. It’s also the case that autonomy increases job satisfaction.

So pushing decision-making down the chain, when done well, means you end up with better people that are happy at their job and are more competitive against others. That’s a pretty big advantage.

Last Updated on June 6, 2025 by Taylor Pearson