Russian revolutionary cum dictator Vladimir Lenin once remarked that:

There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.”

I tweeted this phrase in early March 2020 as the COVID-19 virus arrived in Europe and North America. It seemed at the time that February was more like a century in the past than a few weeks.

Why do we perceive time in this way? Why is it that volatility clusters and some weeks seem like decades while some decades seem comparatively uneventful?

Imagine a giant grid. On each square of the grid is stacked a tiny pile of sand.

We can keep track of how many grains of sand there are on each dot by writing a number on the appropriate square.

The rules for how this system works are very simple:

1. A vertical pile of sand grains can only get to three grains high without falling over.

2. Whenever four or more grains of sand are at the same dot, four grains topple off, one in each compass direction.

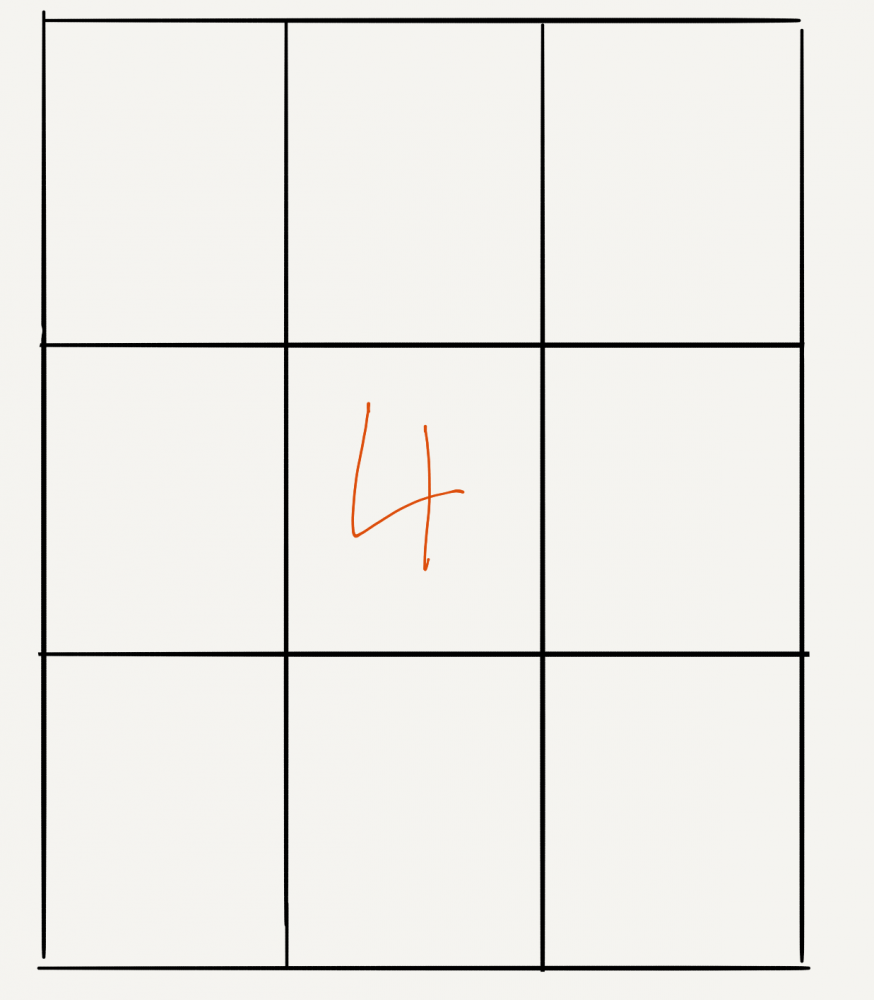

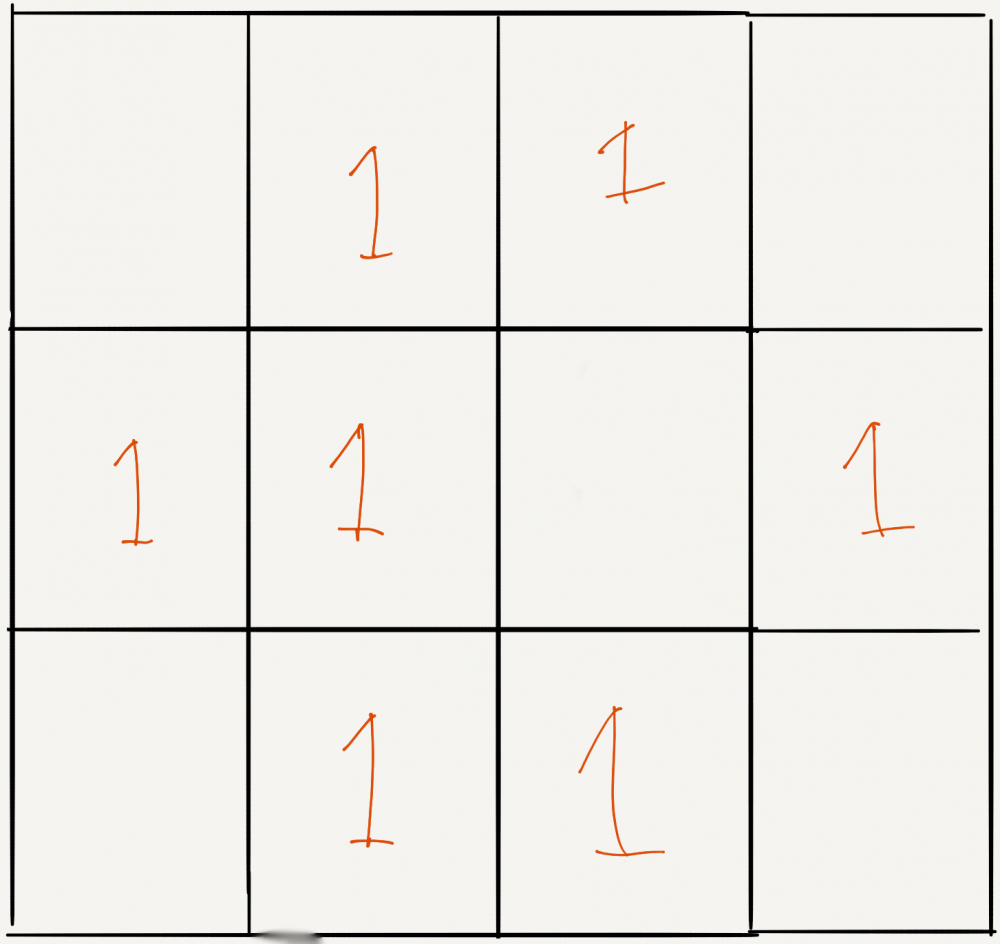

So if you start with this:

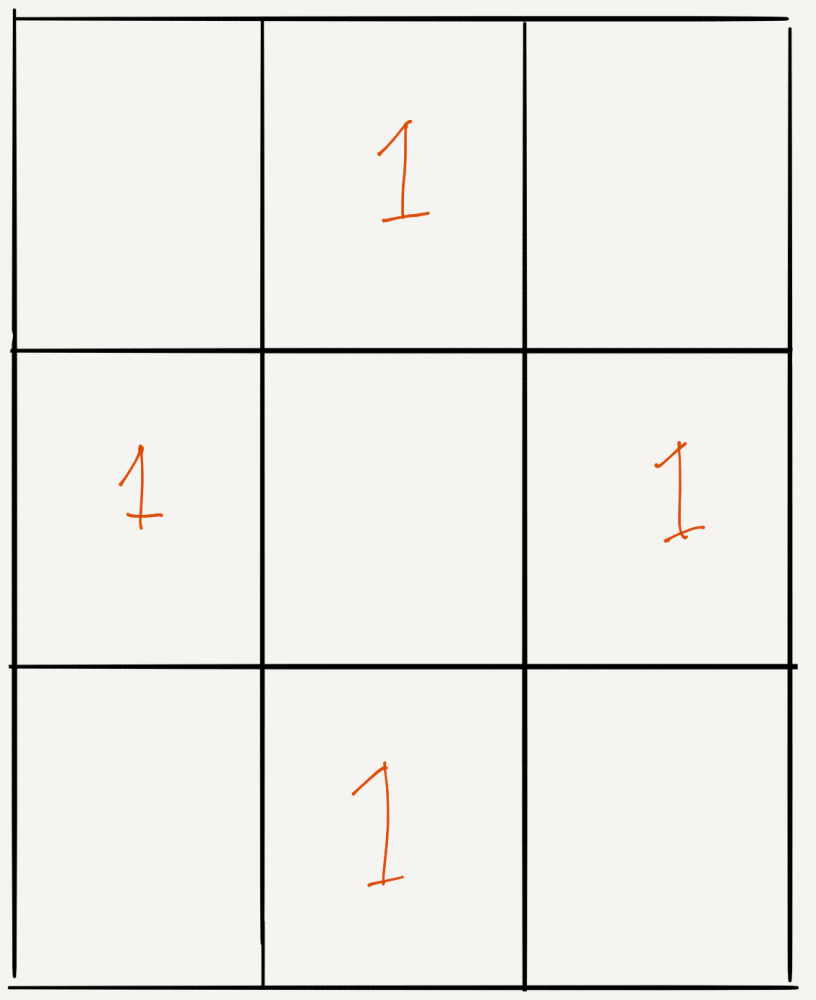

The pile topples and gives you this:

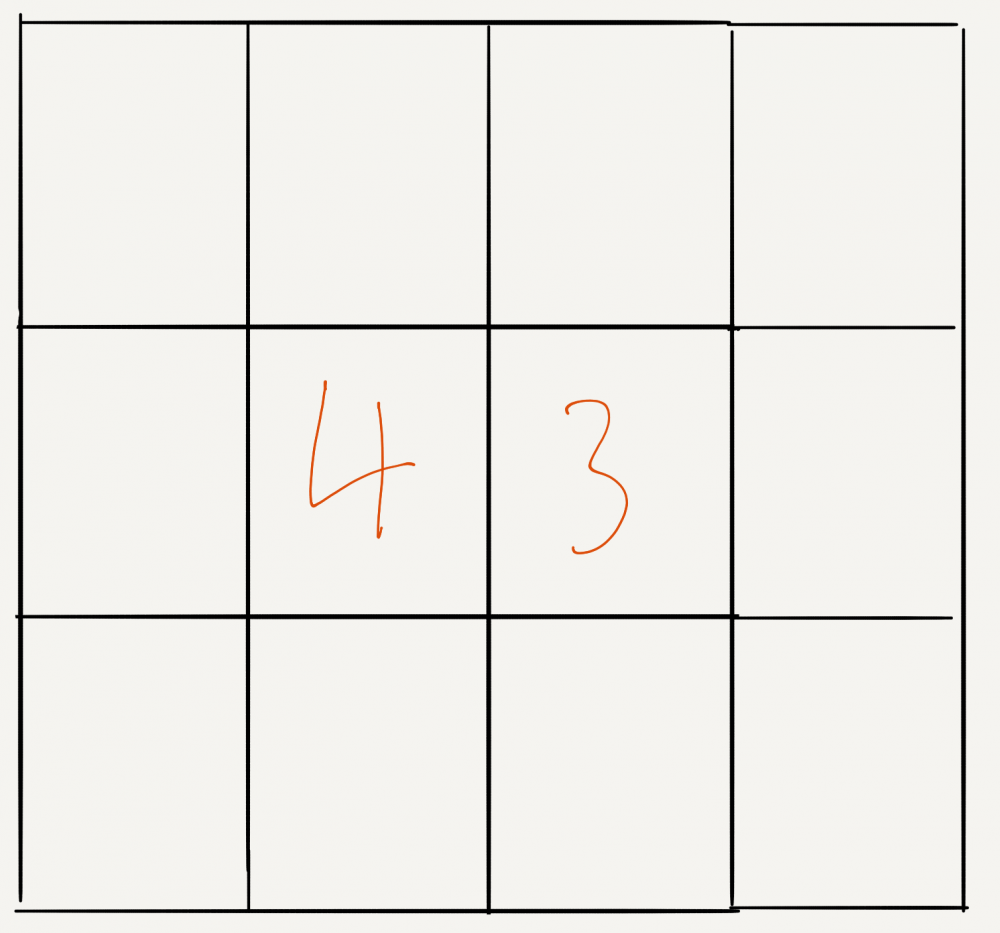

If multiple tiles are overloaded, then you can have a cascade effect. Let’s say you start with 4 grains of sand in one tile and three grains of sand in adjacent tile.

The first pile collapses, spilling over into the adjacent squares.

This pushes the square that previously held only three squares to collapse, cascading into the adjacent squares.

At that point the sandpile is stable. No location has more than four grains, and the process stops.

What’s interesting about this is how a very small change, the addition of a single grain of sand, led to a radical reconfiguration of the board.

Let us take this model as a very, very, very simplified model of how the world works. The board starts empty and, over the course of weeks, months, years, or decades, the sand starts to pile up on different squares of the board.

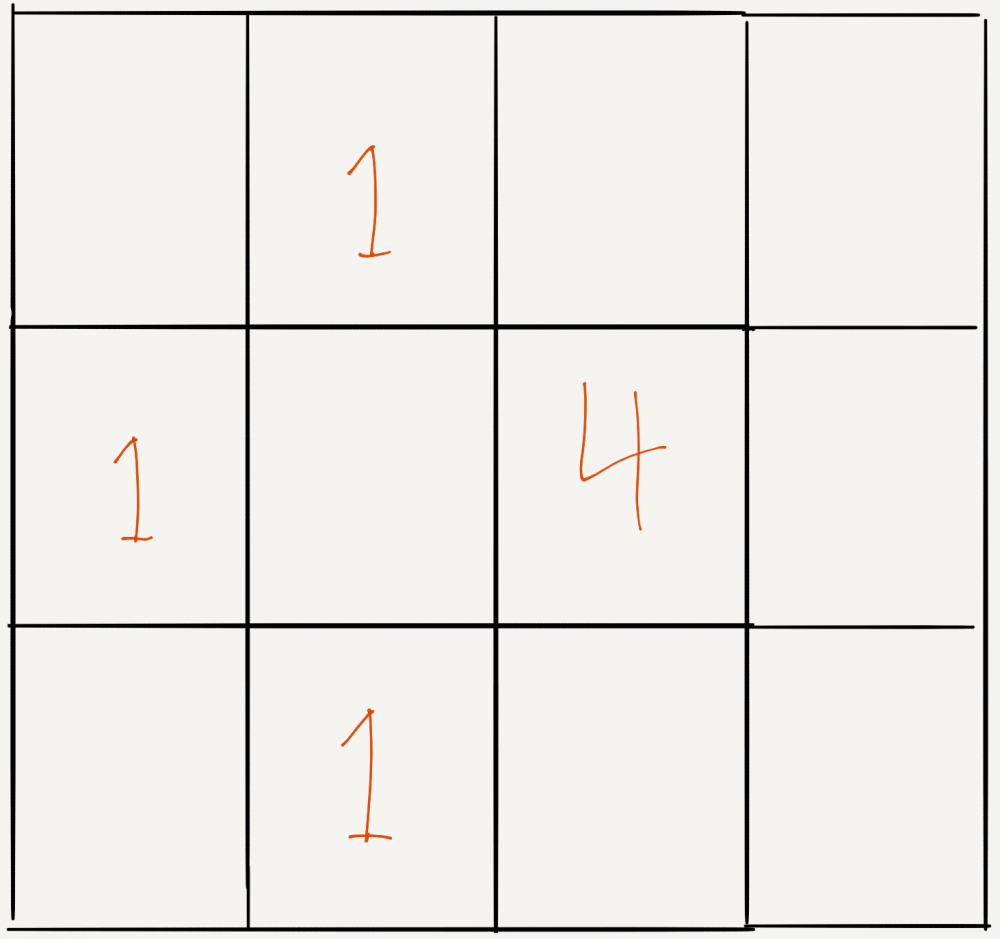

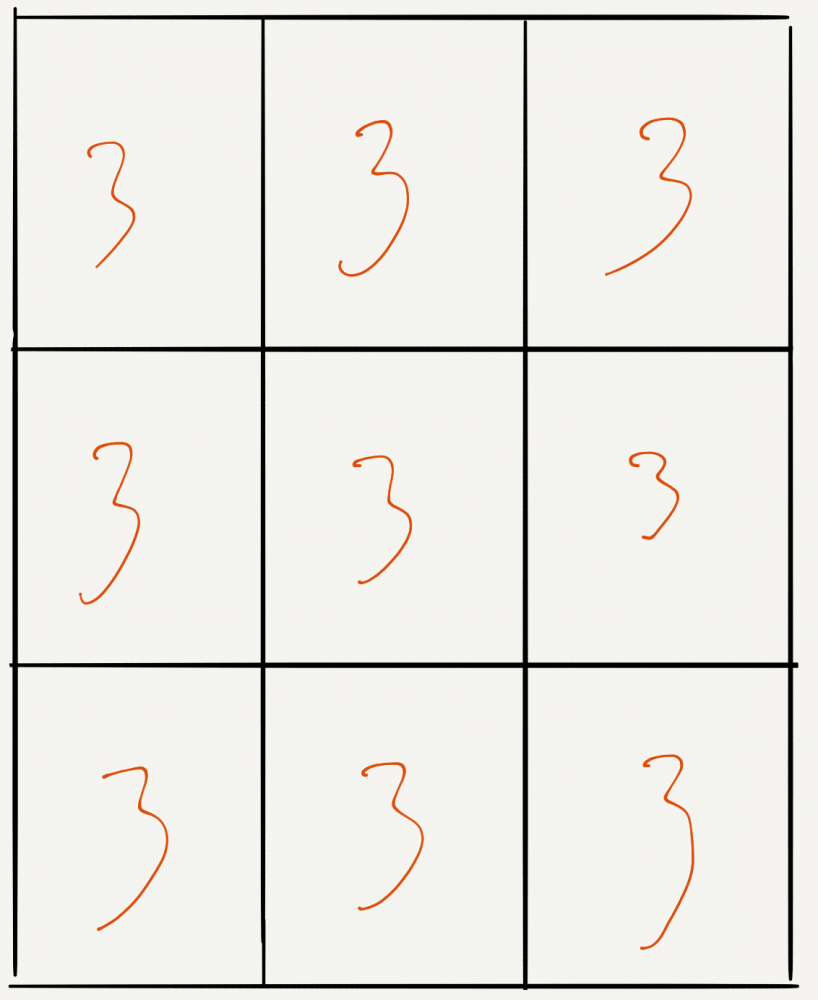

Eventually, the board can reach a configuration that looks something like this.

What’s interesting about this configuration is that all the time leading up to this point has appeared very tame. To the outside observer, there is no noticeable difference between having one and three grains of sand on a single square. Sure, things are changing, but the system remains stable. Everything is fine, right? This is the decades in which nothing happens.

Now, imagine a single grain of sand added to the square in the middle. A seemingly small change will trigger a massive cascade across the entire grid. We observe these periods as the weeks in which decades happen.

In the context of a grid filled with grains of sand, it seems silly to blame the collapse on whichever grain of sand last fell on the sandpile. The issue worth discussing is not which grain of sand caused the cascade to begin, but the configuration of the system. What happened to bring it to the brink of collapse such that a single grain of sand could cause such a massive disruption?

When a system is fragile, harmed by change, then it will eventually blow up. What is important about the grid of all threes is that it is fragile. Any small change will result in an outsized cascading collapse.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand, the Archduke of Austria, was the proximate cause for World War I. Ferdinand’s assassination precipitated Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war against Serbia, which in turn triggered a series of events that eventually led to Austria-Hungary’s allies and Serbia’s allies declaring war on each other, starting World War I.

So, there is a sense in which we can say “Ferdinand’s assassination caused World War I.” But, it’s a narrow and not very helpful sense. If the goal is to prevent a world war, the causes are much deeper seeded and hard to pin down.

The problem was, in part, a much deeper build-up of nationalist sentiment and far more destructive military technology (among many other factors) over the preceding decades. Had the bullet missed Ferdinand, another grain of sand would all but certainly have dropped shortly thereafter. The system was fragile.

However the human brain understands things in terms of narrative and the narrative of “they killed the archduke, we must kill them” is a much easier to spread than the narrative of “there are complex cultural, technological and military forces worthy of deeper consideration and we must think through them all to achieve a stable and resilient consensus.”

Reality has a surprising amount of detail, but our narratives rarely do.

As with a crumbling sand pile, it would be unintelligent to attribute the collapse of a fragile bridge to the last truck that crossed it and even more foolish to try to predict in advance which truck might bring it down. Yet, this is basically the entire business model of ad-based media businesses. Turn on any cable news channel of your choice and you will always find people yelling about their preferred grain of sand.

When a grain of sand falls, people become obsessed with the moralizing the grain of sand (a strictly futile effort) rather than understanding the context and underlying system dynamics. It’s like throwing gas on a fire and then saying the fire was wrong to be there. It’s asinine.

Pointing fingers over the grain of sand and arrogantly proclaiming they saw the grain of sand coming are all responses motivated by a speaker trying to feel self-important and lacking any sense of proportion.

The real work is not so easy nor self-satisfying. It is the messy, complex work of understanding not what happened with the grain of sand but the underlying conditions that made the cascade possible in the first place. It is thinking about and putting into place, systems that are robust rather than fragile.

Last Updated on June 6, 2025 by Taylor Pearson