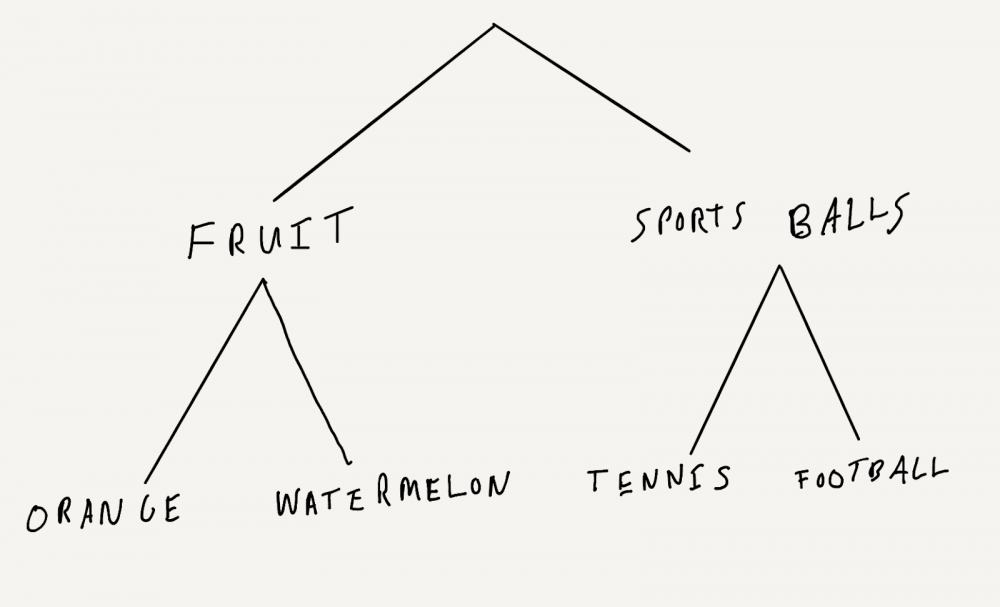

Suppose I ask you to remember the following four objects: an orange, a watermelon, an American football, and a tennis ball. How will you keep them in your mind’s eye?

You will do it by grouping them. Some of you will group them by the type of object they are:

- Two pieces of fruit: the orange and the watermelon.

- Two sports balls: the football and the tennis ball.

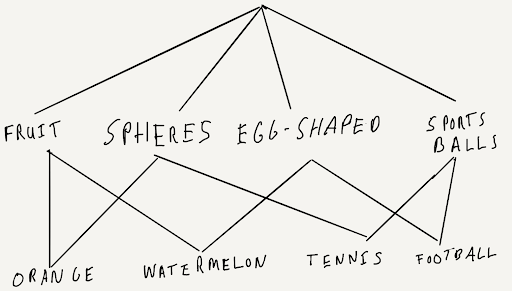

Those of you who tend to think more visually may group them by shape:

- Two small spheres: the orange and the tennis ball.

- Two larger egg-shaped objects: the watermelon and the football.

Both groupings are equally valid. However, they are not mutually exclusive! You could also combine them into a single structure.

However, there is an important difference between the first two diagrams and the latter.

The first two examples here are what we will call trees.

The final example is what we will call a semilattice.

The collection of elements forms a tree if, and only if, for any set of elements that belong to the collection either one is wholly contained in the other, or else they are wholly unconnected.

Consider the set of two items, “watermelon and orange”. In the case of the first example where we grouped the elements by type, these two items are wholly contained in “fruit”.

In the case of the first example where we grouped the elements by shape, these two items are wholly unconnected. Watermelon belongs to the set “egg-shaped” and orange belongs to the set “spheres”.

By contrast, a collection of elements forms a semilattice when there is an overlap in the sets of elements.

The final example is a semilattice. Orange and watermelon both belong to “fruit” but watermelon overlaps with football in belonging to “egg-shaped” and orange overlaps with tennis ball in “sphere”.

Both the tree and the semilattice are ways of thinking about how a large collection of many small systems or elements goes to make up a large and complex system.

Neither is “wrong” per say, but I believe that a great deal of what goes wrong in the world and in our own thinking is the result of seeing complex systems as trees rather than semilattices. If we can learn to think of them as semilattices, I believe it can make us better investors, entrepreneurs, employees, and citizens.

Nearly every system in your life and the world around us is best represented as a semilattice – a set of interrelated elements – as opposed to a tree – a disjointed collection. However, nearly everyone thinks of them as trees.

The tree way of thinking is more popular because it’s a lot easier to keep in your mind. It’s relatively easy to remember and recall the two tree examples above, but comparatively harder to keep the semilattice in your mind. It’s messy looking!

The semilattice is a much more complex and subtle structure than a tree. A tree based on 20 elements can contain at most 19 further subsets of the 20, while a semilattice based on the same 20 elements can contain more than 1,000,000 different subsets. That’s a lot more.

This framework was initially developed by architect Christopher Alexander in his 1965 essay, A City is Not a Tree.

As Alexander saw it, this lack of structural complexity in our thinking, tree thinking, was crippling our cities so let’s start with cities as an example and we’ll go on to look at some other systems.

The way most urban planners represent a city is as a tree. At the top level you have the city, then the neighborhood, then the block, followed by the street and finally the family. Each of these is disjoint from another. Families belong to one street which belongs to one block and that to one neighborhood.

However, this conception of a city does not actually match the social structure which exists in reality. If you ask someone to name their best friends and then ask them in turn to name their friends, they will not name everyone their block.

They all name different people scattered around the city, many of which are likely unknown to the first person you asked. These people would again name others, and so on outwards.

If we were to make a diagram of all these connections, it would in no way correspond to a tree diagram of streets, blocks and neighborhoods. There are virtually no closed groups of people in modern society. The reality of today’s social structure is thick with overlap, a semilattice.

When we conceive of a city as a tree, it suggests a hierarchy of strong, closed social groups. Indeed, the very construction of modern cities promotes loneliness and isolation. Most modern cities are built with “subdivisions.” The word “division” is literally in the name of the structure. Who would not feel divided living in a division?

A tree structure implies that within this structure no piece of any unit is ever directly connected to other units, they all move through the tree hierarchy. This is a horribly impoverished way to view society.

Consider the difference between an older city, built and evolved over centuries, such as London (left), and one built much more recently and over a shorter period, San Diego (right).

Which of these cities appears to more embody the tree structure and which the semilattice? San Diego is most clearly a tree, with straight rows of streets, easily divided up into separate segments. One can quite easily imagine the central planner sitting down to divide up the streets, blocks, and neighborhoods.

London by contrast is much more a semilattice – it is hard to tell where one area ends and another begins, it is a more overlapping set of elements.

It must be emphasized the semilattice structure is not less orderly than the rigid tree, but more organized. The semilattice, while appearing “messier” viewed from the top-down, represents a thicker, tougher, more subtle and more robust structure. Not surprisingly, cities with a more semilattice structure tend to be more social, vibrant places to live.

Consider the notion of play and how children play in a city. Tree thinking leads to the separation of recreation from everything else. This has crystallized in our real cities in the form of “playgrounds”. The playground, asphalted and fenced in, is premised on the idea that play exists as an isolated concept in our minds.

The playground has nothing to do with the life of play itself. Play itself, the play that children practice, goes on somewhere different every day. One day it may be indoors, another day inside a friendly corner store, and another day down by the river. How many of your childhood memories of play happened in a playground? I have not one memory of being in a playground. I played in the driveway, in the neighbor’s bamboo grove, and in the pecan orchard in front of the school two blocks away.

The concept of play should not be isolated from the rest of life or of the city but is integrated into it. The trail along the river is a place for children to play, for teenagers to sneak off to be away from their parents, for runners to exercise, for dog owners to take their dogs out for a walk, and for workers to ride their bikes to work. Each physical place represents an element, a node, in a vast semilattice structure.

When we attempt to reduce the semilattice down to a tree, it greatly cripples the ability of our cities to function effectively, it reduces them to a soulless and mechanical concrete jungle in which no human actually wants to live.

This is not merely the case with cities, but nearly everything in our lives. It is this lack of structural complexity in our thinking, this tree thinking, which cripples our ability to function effectively in the world and for the systems in the world to function effectively around us.

I think we tend to engage in tree thinking because grouping and categorization are pretty primitive psychological processes. Our mental concepts grow out of our physical reality. Just as you cannot put a physical thing into more than one physical pigeonhole at once, so, by analogy, the processes of thought prevent you from putting a mental construct into more than one mental category at once.

Indeed, the powerful marketing concept of positioning is based on this.

When consumers buy, they go through a two-step decision process:

- They pick the category (e.g., SUV)

- They pick brands (e.g., Lexus, Honda, Mercedes)

By owning the category, you are able to short-circuit the buying process. They don’t think about comparing you against another company; they see you as the best option in your category.

Study of the origin of these processes suggests that they stem essentially from the organism’s need to reduce the complexity of its environment by establishing barriers between the different events that it encounters.

And, indeed, reality has a surprising amount of detail. So much detail in fact that even the incredibly powerful human brain cannot even begin to conceive of all of it. However, in any complex system, extreme compartmentalization and the dissociation of internal elements are the first signs of coming destruction. In a society, complete dissociation is anarchy, a breakdown in all the bonds which enable higher functioning. In a person, dissociation is the mark of schizophrenia.

Though the tree is the most legible representation of a complex system, our social, economic and political systems cannot and must not be seen as trees. We must resist the easy path and do the difficult work to see them as semilattices. (I’ve previously referred to this as kaleidoscope thinking. Though one is always looking at the same elements through a kaleidoscope, one can view them in many different ways and this is true of basically everything.)

As investors, we tend to think of our portfolios as trees, but they are semilattices. Thinking of portfolios as trees leads to deeply problematic issues, a cult of stock-picking with no concern for the broader portfolio. If I ever tell someone I work in investment management, the first question is always “what stock do you like?”

Not once at a cocktail party has anyone ever asked me “what portfolio of assets do you think offer the best risk-adjusted returns given the many potential paths which markets could take?” Obviously this is a mouthful, but some version of this question is the only question you should ask.

“What stock do you like” is tree thinking, it is focusing on the individual elements at the expense of the whole. Semilattice thinking means looking not at the individual elements but the combination of elements as a whole.

Diversification math shows that you can combine lower returning individual assets for a higher expected value of the portfolio’s return.

If you like this stock, can you then find something else you might not like as much, but should behave in a negatively correlated way? This is vastly more valuable and vastly underappreciated by investors at large.

The returns of a portfolio are “other than the sum of its parts” – combining uncorrelated or anti-correlated assets can improve portfolio-level returns.

We think of companies as trees, but they are semilattices. Consider a company with a marketing, engineering, and design departments. The tendency is to conceive of this as an org chart (a tree) and separate out these departments. Though each has a head, you cannot forget that they are all intimately connected.

A junior marketing person should not need to go through their manager to ask a designer or an engineer for help on a marketing initiative. Nor should an engineer need to go through their manager to get front-end design help from a designer or copy suggestions for a tooltip from the marketer.

Edward Banfield, in his book Political Influence, gives a detailed account of the patterns of influence and control that have actually led to decisions in Chicago. He shows that, although the lines of administrative and executive control have a formal structure which is a tree, these formal chains of influence and authority are entirely overshadowed by the ad hoc lines of control that arise naturally as each new city problem presents itself.

This is a feature, not a bug! Indeed, most companies tend to try and enforce a tree structure but the frontline people tend to voluntarily form a semilattice because they intuitively know it is the more effective way to get things done.

The concept of an organizational chart is a tree when it is better represented as a semilattice. Drawing it as a semilattice is much more challenging and complex, but also more accurate, and, in the long run, effective.

We think of our lives as trees, but they are semilattices. Consider the phrase “work/life balance” – it implies these are two wholly separate objects which must be balanced against one another, a tree way of thinking.

It is impossible and counterproductive to try and completely keep people’s personal lives out of work. Of course, someone’s performance at work will suffer when their child is sick, or a loved one dies, or their partner is laid off. The solution is not to ignore it, but to address and discuss it like emotionally functional adults.

However, overlap alone does not give structure. It can also give chaos. There are many incoherent ways to draw an org chart or construct a portfolio that can be visualized as a semilattice.

You can model your garbage can full of trash as a semilattice. That does not make it helpful. Designing something as a semilattice does not insure that is effective, but designing it as a tree does ensure that it will be ineffective and fragile.

To have structure, you must have the right overlap. As the relationships between functions change, so the systems which need to overlap in order to receive these relationships must also change. The recreation of old kinds of overlap will be inappropriate, and chaotic instead of structured.

Cities, companies and portfolios can and should evolve.

Semilattice thinking is at the heart of the concept of strategy. The effective strategist merely sees the shifting semilattice better than their competitors do. Once that is achieved, winning is merely procedural.

Though he didn’t use these terms, military strategist Sun Tzu deeply understood the concept of conceiving of war as a semilattice composed of overlapping political, economic, geographical, cultural and military elements.

It is this ability which the best strategists (be they generals, politicians, entrepreneurs or managers) have in common with one another. It is their ability to see what is illegible to others.

Sun Tzu’s famous work The Art of War is a book nominally about, well, war. It’s kind of deceptively titled though. A more accurate title would be “The Art of Not Going to War Unless You Really Can’t Avoid It And Then Still Avoiding Fighting as Much as Possible.” And indeed, this is the essence of the whole thing! To see war (or anything else) as separate from other affairs is the great mistake of many a failed strategist.

We are all elements embedded in the vast and incomprehensible semilattice that is our universe. To seek to understand it leads to no final resting place of the mind; no moment of smug clarity. Wisdom is no more than realizing how unwise we are and how far we have yet to go. Once we arrive at that starting point, true progress may yet follow.

Last Updated on June 6, 2025 by Taylor Pearson