My favorite movie on marketing is You’ve Got Mail with Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan. The movie teaches one of the most valuable marketing lessons I’ve learned: what happens when speed of implementation meets the law of shitty click throughs. All you need to know about the movie is this: in 1998, people were excited to get email.

Marketers who were using email marketing in 1998 often saw 90% Click-through rates (CTR), the number of people clicking on links in their emails. Average email click-through rates today are around 3%, a 3,000% drop. A 10% CTR is exceptional.

The steady decline in click-through rates happens to every marketing channel.

The first banner ad ever, on HotWired.com in 1994, got a 78% click-through rate. The average banner ad CTR today is 0.17%, 45,800% lower (not a typo).

The cost of advertising on Google Adwords has gone up every year since the platform launched, and the click-through rate has gone down. Same with Facebook ads.

It’s not just paid marketing channels, it’s every marketing channel. Organic reach on Facebook has declined in lockstep.

This phenomenon is known as The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs:

Over time, all marketing strategies result in shitty clickthrough rates.

The implication is that benefits of a new channel overwhelmingly go to those who optimize for one thing: speed of implementation. People who move fast and break things win.

If you gave me the choice between having the best professional email marketing copywriter in the world write emails today or having an eleven year old write them, but he gets to go back in a time machine and get 1998 click-through rates, I would absolutely take the eleven year old (it’s not even close).

Speed Compounds

Speed of implementation alone often matters more than every other factor combined. This is something I’ve observed anecdotally in myself, clients, and friends — but it’s not intuitive as to why.

The short answer is compound interest.

Let’s do a thought experiment. Take two people, and say one is just a bit faster to adopt new marketing channels than the other. Hold all other factors equal.

Person 1, we’ll call him Zuck in honor of Mark Zuckerberg’s “move fast and break things”, adopts the new medium when it has a CTR of 20%.

Person 2, we’ll call him Henry,1 adopts the new medium when it has a CTR of 10%

You would expect Person 1 to do better. How much better? 20% is twice as much as 10%, so you’d probably think twice as good. That was my first intuition.

Let’s play it out.

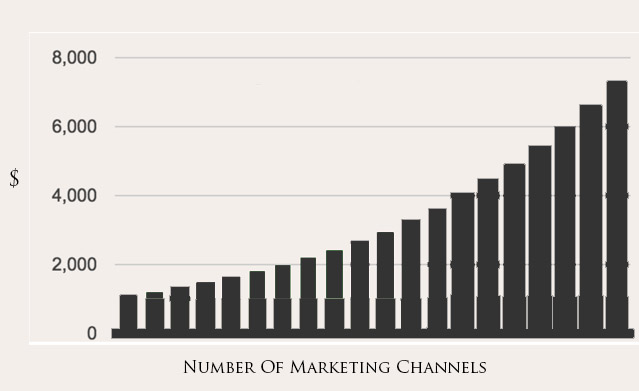

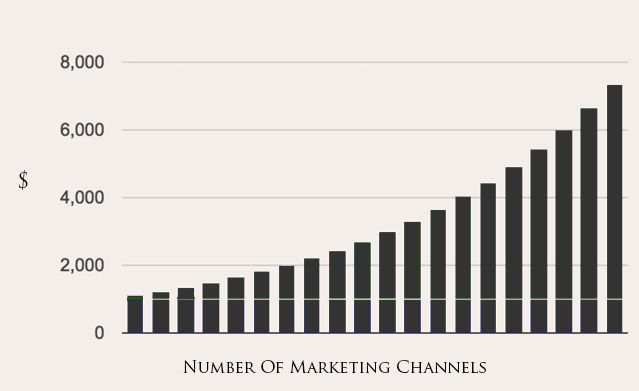

Speed of Implementation After 10 Channels

If they went through 10 marketing channels each and both started with $1,000, then Zuck would end up with a 2.68x better return than Henry. We’ll call this number (2.68), Zuck’s speed premium. It’s the advantage he gains by being faster than Henry.

Zuck = $ 7,268

Henry= $ 2,707

Zuck’s Speed Premium =268%

This is slightly better than we might expect. Let’s keep running the experiment for a few more channels

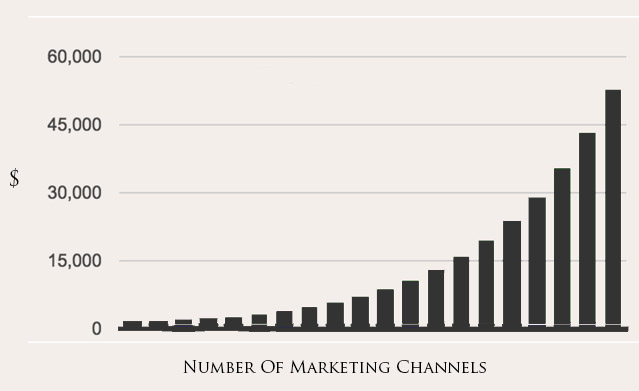

Speed of Implementation After 20 Channels

After they’ve gone through 20 marketing channels, Zuck has now ended up with a 7.21x better return than Henry.

Zuck = $ 52,828

Henry = $ 7,328

Speed Premium = 721%

Woah! That’s a bit more than you would expect!

What happened? Compound interest happened.

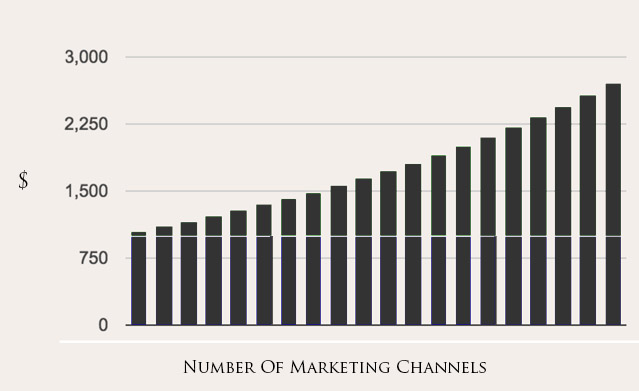

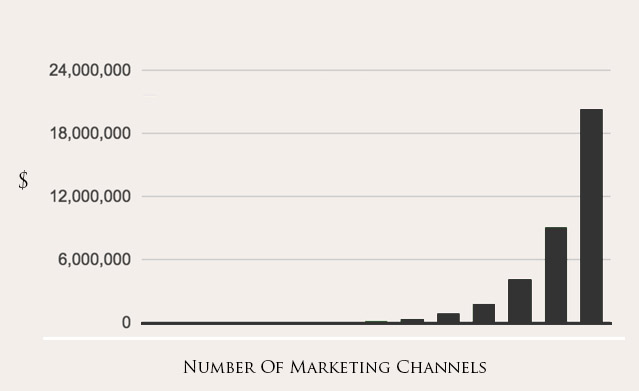

Speed of Implementation After 50 Channels

Zuck = $ 20,283,868

Henry = $ 145,370

Speed Premium = 13,900%

As you add more and more iterations, the speed premium gets enormous.2

There’s a reason Y Combinator CEO Sam Altman says “the best founders seem to be fast at everything.”

I can’t think of any other factor that correlates more strongly with company growth than speed of implementation that I’ve seen.

If Moving Fast is so Valuable, Why Do Most People Move Slow?

The reason most people don’t implement fast is a psychological bias called loss aversion.

The best way to understand loss aversion is to imagine someone offering you a 50/50 gamble. You will flip a coin and heads you win, tails you lose.

There’s a catch. The minimum bet is $5,000.

What’s the lowest payout you could tolerate, in order to place the bet? Would you take slightly better than equal odds? Heads you win $6,000 and tails you lose $5,000?

Or would the pay out have to be better? If the deals Heads you win $10,000 and tails you lose $5,000, would you do it?

In several experiments, researchers found participants usually would not participate for less than 2-2.5x; that is you have at least a 50% chance of losing $5,000 and winning $10,000.3

This is clearly irrational, so why do we do it?

It’s a part of our evolutionary heritage. In a life or death situation, you should be risk averse.

If you are walking through the African Savannah and you hear a rustle in the bush and you estimate there is a 95% chance it is a delicious piece of food to eat for dinner and a 5% chance it is a lion, your ancestors ran away. The ones who didn’t were eventually weeded out of the gene pool and became a snack food.

The proper way to think about it is to think about is in terms of affordable loss.

Affordable loss means just that, can you afford to be wrong? On the Savannah you can’t. On marketing channels, you can. If you’re wrong and spend a few hundred bucks testing a new marketing channel, it doesn’t kill you, if you do it systematically, you get the kind of speed premium that Zuck did.

What marketing channel do you believe in that few other people do?

What’s a good heuristic to find the new marketing channel that’s going to reward you?

It’s an adaptation of venture capitalist Peter Thiel’s question for finding great companies: What marketing channel do you believe will be huge that few other people do?

This is usually a courage problem. The hardest part about email marketing in 1998 wasn’t sending an email, it was having the courage to invest in the internet when Newsweek was calling it a “fad.”

Mark Manson, a popular blogger, started doing Facebook marketing in 2013 when many people still thought it was a fad. The joke is on them as his readership, built primarily from Facebook traffic, recently made him a NYT bestselling author.

The Speed Premium applies to almost everything.

The reason the speed premium is important is because most domains exhibit the same phenomenology as marketing. They follow the law of shitty click-throughs.

Whenever I give people career advice, one of the first things I tell them is to start sharing their work publicly and build an audience. Frequently the push back I get is “well, not everyone can build an audience. How can everyone have hundreds or thousands of people that follow their work?”

They can’t! But that doesn’t mean you can’t do it.

There is always a time “to do” something. If you wanted to start a corporate bank, you missed it. The time was 100 years ago, when JP Morgan did it. Could everyone have done it? Nope. But that didn’t stop Morgan. Now I look out my window towards Manhattan, and see a 52 floor building on Park Avenue with his name on it.

Not everyone could start a steel company or an oil company a hundred years ago, but Carnegie and Rockefeller were too busy making money hand over first to notice.

If you want to start an internet company, now is a pretty good time. In 100 years, the internet may not be a very good place to start a business.

That’s a good reason to start now, not to wait.

Speed is a muscle.

Learning to move fast is just like just like getting stronger.

To get stronger, you want to lift a little more weight than the last time you went to the gym. If you lifted 50 pounds last week, you want lift 55 this week and then 60 next week.

If you don’t add weight, you never get stronger.

If you add too much weight, too fast, you get hurt.

If you gradually, but consistently, add weight, you get strong

A good rule of thumb is that the weight you are lifting should always make you feel slightly uncomfortable.

If you aren’t a little bit nervous before you pick up the weight, it’s probably too light.

If you are terrified you’re going to hurt yourself, it’s probably too heavy.

In the same way, you want to always be moving so fast that you are slightly out of control.

Not so fast that you lost control and get hurt, but you should feel slightly uncomfortable about how fast you are moving.

Speed is a muscle. Train it.

Last Updated on June 7, 2025 by Taylor Pearson

Footnotes

- As in Henry David THOREAU which is a homonym for thorough which is the reason most people give for being late to adopt new marketing. Yea, it’s a stretch.

- You can play with your own calculations using a calculator like this one (link tohttp://www.helpfulcalculators.com/compound-interest-calculator)

- Source:

Kahneman, Daniel (2011-10-25). Thinking, Fast and Slow (p. 292). Macmillan. Kindle Edition.

This article does an excellent job of clearly illustrating the benefits of first mover advantage in a tangible way. I think everyone hears about “first mover advantage” at an abstract level, but very few truly understand the compound effect it can have.

Which explains why, when you look at some people “at the top” in a given industry (especially in marketing), it’s not readily apparent WHY they’re at the top. You can find inconsistencies and contradictions in their content…glitches and errors in their products, but it’s because they optimize their business for speed, not perfection.

By the time anyone has even noticed any imperfections, they’ve already moved on to the next channel.

Great post

“By the time anyone has even noticed any imperfections, they’ve already moved on to the next channel.”

Yes! I see this all the time. Common mistake is to view the channel as the source of success of success and not speed. Instagram is the secret vs. being an early mover to any channel is the secret.

Great article Taylor! Enjoyed the read and I completely agree with you about ‘shitty clickthroughs’ lol. For some time, I’ve been seeing the death of e-mail and online ads but business owners insist on throwing their money at that black hole!

As a Digital Marketing & E-Commerce Specialist, I deal with analytics and click-through rates everyday, and they are not pretty. I also believe it comes down to the person’s ability to adapt and change to new technologies constantly. Businesses however, value ‘best practices’ more than trying new approaches so what I have found is that working with Innovative Entrepreneurs is the best fit for someone like me who adjusts their approach to optimize strategies.

It’s also good that you note the ROI difference between ‘conventional’ approach to ‘first mover advantage’ like Jordan mentioned before me.

Very well written. Thank you for the insight.

Hey Joyce,

That’s interesting. I’m mostly bullish on email (though not banner ads).

I think there’s some subtleties here that I didn’t manage to tease out in this article between the Lindy effect (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lindy_effect) and first mover advantage.

The people who succeed seem to straddle the two well. E.g. People who built up huge FB followings and moved those followers onto email did really well. Those who kept those followings only on FB have slowly seen their reach disappear.

Not sure what the distinction is there. Email seems unique in that no one “owns” it in the way other platforms are owned?

If you deal at all in foreign markets, this is even more apt. I get CTRs 100x higher in undeveloped markets – something people hardly ever keep in mind when they consider the returns in those countries.

Great point. Didn’t even think about this.

Would you take into consideration the wasted time being an early adopter to channels that never prove out a positive ROI?

Yes. It’s worth considering but I think it’s greatly exaggerated. For one, it doesn’t take that long to figure out a channel. I got a sense for snapchat in an hour of messing around with it. Didn’t feel like a fit for my brand/content but not much of a cost.

It also seems like there is a certain logic that you can learn which transfers well. The people who “got” Facebook first were usually myspace/friendster users. They understood the logic of it already and saw the potential.