Toyota for the last 20 or 30 years has been the benchmark car maker for reliability. This seems normal now, but it’s important to know that Toyota used to make really, really terrible cars. In the 1960s, the heyday of the American automotive industry, Toyota’s reputation was about as bad as it could have been. Then, by the early 80s, they were the best cars in the world and parents across America were enrolling their kids in Japanese classes.

What happened?

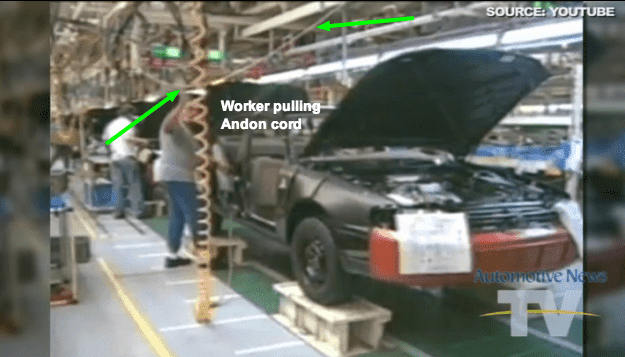

A lot of things happened, but one particularly important one was the Andon Cord.

The Andon Cord was a rope that hung in Toyota factories. Nothing fancy, just rope like you’d use to tie down luggage to the roof of your car.

It was special in one way: when pulled, the rope would instantly stop all work on the Toyota assembly line.

And, here’s the craziest thing about it: anyone had the right to pull the Andon cord at any time.

If any human being in the manufacturing plant wanted to totally halt production, they were free to pull the Andon Cord.

In fact, they made it part of your job. Whenever a worker saw a problem with a car, they were required to pull the cord and stop the line.

Once all production was halted, a team leader would immediately go ask why the rope was pulled. Then, together, the leader and the team could work to solve the problem and restart production. Not only did they fix the problem, they figured out what was causing the problem so it didn’t happen again.

The process of stopping a system when a defect was suspected originates back to the original Toyota System Corporation to something called Jidoka. The idea behind Jidoka is that by stopping the system you get an immediate opportunity for improvement, or find a root cause, as opposed to letting the defect move further down the line and be unresolved.

What happened in the short run after implementing the Andon Cord was that Toyota’s productivity plummeted. But, their quality started to improve. Slowly, but surely, every year they were making thousands of marginal improvements. Not just to the cars, but to the process. That’s the key.

They weren’t focused on building any individual car better so much as they were focused on improving the system which made cars. Every time the Andon Cord was pulled, Toyota’s manufacturing process got a little bit better. Within seven years their process was nearly flawless and they were producing the best cars in the world.

What’s interesting is not just the use of the Andon cord, but how Toyota thought about it.

The first cultural element is the level of control it gave to factory workers. Most analysis of this type of cord might assume this was implemented as a safety cut off switch, a “break glass in case of emergencies” type thing.

When asked about this process by many other companies, Toyota took issue with the idea that employees had a “right” to pull the cord. From Toyota’s perspective, employees were obligated to pull the cord if they discovered a problem with production.

It was a tool to instill a sense of ownership with the frontline workers that best understood what was going on. And they had real ownership. Pulling the Andon Cord didn’t send a message asking permission to stop the line which went up to the plant manager, the pull actually stopped the entire production line. They gave frontline workers that level of control.

This is scary! But, as Toyota shows, it’s also a huge long-term advantage to push decision making down the chain of command. The people actually doing the work understand the details much better than the manager looking at it on a high modernist spreadsheet.

The second important cultural aspect is that when the Andon Cord was pulled a team leader would immediately “go-see” the issue by visiting the workstation. Toyota lived by this “go-see” culture. In most organizations, a team lead might just call the workstation to find out what was happening. The “go-see” removes a lot of potential for miscommunication. If a picture is worth a thousand words, a video or in-person inspection is worth 10,000.

In the case of knowledge work type organizations, I think most organizations underuse screen sharing by a factor of somewhere between 10x and 100x. One of the largest sources of inefficiency in most companies is people talking past each other because they aren’t even on the same page of what they are talking about. I suspect 20% of all meeting time could be eliminated by simply asking “Can you please share your screen.”

Words are abstractions. Useful abstractions, but abstractions nonetheless!

A third important cultural aspect of the Andon Cord process at Toyota was that when the team leader arrived at the workstation, he or she thanked the team member who pulled the cord. This was an unconditional behavior reinforcement. The team member did not, or would never be, in a position of feeling fear or retribution for stopping the line. Quite the contrary, the team member was always rewarded verbally. What Toyota was saying to the team member was, “We thank you and your CEO thanks you. You have saved a customer from receiving a defect.” Moreover, they were saying, “You have given us (Toyota) an opportunity to improve for that we really thank you.”

The Andon Cord was a way of increasing the compounding for Toyota. Getting 1% better every day compounds to a lot and doing it for a decade can take you from one of the worst car makers in the world to the best.

Another key point in this process was that even if the team leader knew a better answer, Toyota felt that a solution from the team member was a better outcome. If the problem is not understood at the line level, that is the team member/mentee, then the problem was not solved. Again, decisions were pushed down the chain of command.

The practice of allowing people to pull the Andon Cord has two powerful implications. First, the workers feel trusted and empowered to take part in quality assurance, and this contributes to a culture that invites everyone to take pride in the plant’s output. Everyone really did have an impact on the final output of the plant.

People tend to grow or shrink to their role. When you treat people like children incapable of making decisions, they will often shrink to that role. When you treat people like adults and invest power in them, they will often rise to it.

The second is that it dramatically increases the rate of improvement. Because reality has a surprising amount of detail, the person best situated to make a decision is usually the one closest to the process. That person has a level of tacit knowledge that gives them an intuitive understanding which someone further away lacks. By putting the Andon Cord in the hands of all the workers, Toyota was effectively maximizing the use of that local knowledge. Everyone knew they had the ability to actually improve the process and so they did.

The “cost” of implementing this system is that you have to hire good people and trust them to make decisions. As many American car makers found out, the “cost” of not implementing it is you get outcompeted by organizations like Toyota that trust their people so you don’t have much of a choice in the long run.

Toyota isn’t the only company to make use of the Andon Cord. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the other company which uses it is one of the fastest-growing companies in history: Amazon.

Jeff Bezos described in a 2013 letter to Amazon’s shareholders a practice he called the Customer Service Andon Cord. This was an established practice of metaphorically pulling an Andon Cord when they noticed a customer was overpaying or had overpaid for a service. They would automatically refund a customer, without the customer even asking, if the service delivery was suboptimal.

When a customer calls an Amazon representative to report a problem or defect in a product, the rep has the ability to “pull the cord.” He or she can completely remove the product from distribution until the problem has been fixed.

Ultimately, companies that survive will be the ones that let people pull the Andon Cord. And the people that survive will be the ones that have the courage to do so. Pull the cord.

Last Updated on June 6, 2025 by Taylor Pearson