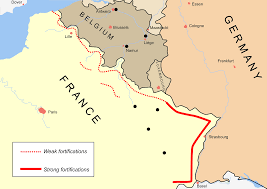

The Maginot Line was a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles and weapons built by France in the 1930s to deter invasion by Germany.

When it was built, the Maginot Line was believed to be one of the most significant innovations in national defense. Foreign leaders came from all over to tour it.

It was an impressive-looking series of fortresses and railroads, resistant to all known forms of artillery. It had underground railways that made it invulnerable to bombings and tank fire and state-of-the-art living conditions with air conditioning for stationed troops.

French military experts extolled the Line as a work of genius that would deter German aggression. They believed that it would both deter Germany and, in the case of an attack, it could slow an invasion force long enough for French forces to mobilize and counterattack.

The Maginot Line extended into the border with Belgium but stopped at the Forest of Ardennes because of the prevailing belief among experts that Ardennes was impenetrable.

To spoil the ending, the Ardennes was not impenetrable.

At the start of the war, The Germans deployed a small force to the Maginot Line as a decoy then sent a million men and 1500 tanks through the “impenetrable” Ardennes.

A rapid advance through the forest encircled much of the Allied forces, resulting in a sizeable force being evacuated at Dunkirk leaving the forces to the south unable to mount an effective resistance to the German invasion of France.

The Germans attacked on May 10th and by June 14th, Paris fell to the German army. On June 22, the French government signed an armistice. A feat that had not been accomplished in five years of bloody trench warfare in the First World War happened in just over five weeks.

Why did this happen? Why were the French so wrong and defeated so quickly?

The Army is Now Fully Prepared to Fight the Previous War

They fell victim to The Maginot Line Problem: they learned the lesson of the First World War much too specifically: “The Germans came across right here so we are going to build a big wall there”, and failed to update their thinking as technology and the world around them changed.

Though the Maginot Line is a particularly good example, this is a much more general class of problem. Some sort of shock to a system (be it a military system, economic system, personal personal system, etc.) happens. The system is then redesigned to prevent that specific problem from happening again without thinking deeply about the more general system dynamics.

In his alternately hilarious and insightful book Systemantics, author John Gall noted that:

[There is a] strong tendency to apply a previously-successful strategy to the new challenge: THE ARMY IS NOW FULLY PREPARED TO FIGHT THE PREVIOUS WAR.

Moving through the Ardennes using World War I era technology would have been a futile effort, but the advent of tanks among other new technologies made it much more feasible.

As the French poured more and more resources into building the Maginot Line, the Germans did the opposite: they looked at the technologies that had come out since the First World War and worked to develop a new model of warfare that could take advantage of it. It became known as Blitzkrieg.

Compared to the slow-moving and bogged down trench warfare of the First World War, Blitzkrieg moved fast and dynamically. In their five week invasion, the Germans broke through the French lines over and over, never getting bogged down in trenches as the French had expected at the Maginot Line.

Blitzkrieg was enabled by a few key technological developments.

The first was the internal combustion engine and tanks. The Germans realized that they could use tanks and motorized artillery that would be able to quickly probe points in the enemy line.

Tanks could both move faster than infantry or even traditional horse cavalry, were better shielded, and could easily run over the concertina wire that had been used in World War I trench warfare to slow down infantry.

That meant tanks could lead the charge more effectively. Once the tanks broke through, the infantry could quickly follow behind the tanks in armored personnel carriers instead of running to their deaths across the no man’s land common to World War I battlefields.

Early World War II era tactical aircraft couldn’t do much damage on the ground, but the advent of radio technology meant that planes could provide intelligence via radio on troop movements to reduce the “fog of war” that tank commanders experienced. When combined with their much faster speeds and armor, this made it relatively easy for tank commanders to know where the most likely points to break through the French line were and concentrate on them.

Once tanks had broken through, motorized troop transport could move infantry in behind the tanks much faster. This made it possible to flank the enemy quickly and establish their position on the gained ground. There was no way to do that with horses over hundreds of miles since horses would get tired and required rest that left the enemy time to regroup and establish a new line.

The Maginot Line Problem has at least two aspects.

One is that lessons tend to be learned in much too specific a way and not generally enough. The correct lesson from the First World War was that the French should be prepared for German aggression, but the French didn’t prepare broadly, they just built a huge concrete wall exactly where the Germans had tried to cross last time – basically playing the world’s most expensive and tragic game of whack-a-mole ever.

Secondly, the Maginot Line, designed to very effectively fight the last war, had delivered a false sense of security. It was not just problematic that the French built the wrong defensive barrier, it was that they were so sure they had built the right one, lulling them into a fall sense of complacency.

As my dad frequently liked to remind me growing up: “It ain’t what you don’t know that hurts you, it’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

A country with many laws is a country of incompetent lawyers

This is not a phenomenon isolated to War, but broadly applicable to any complex system: be it a company, investment strategy, or organism.

Peter Drucker noted that:

By far the most common mistake [made by business leaders] is to treat a generic situation as if it were a series of unique events; that is, to be pragmatic when one lacks the generic understanding and principle.”

The effective entrepreneur or executive does not need to make many decisions. Peter Thiel said that the only thing that the best leaders do is to make four big, correct decisions per year.

Whenever a seemingly unique event happens, you have to ask: Is this a true exception or only one manifestation of a broader problem? The tendency of most people is to see it as a one-off occurrence rather than a symptom of a broader problem.

One business leader that understood this well was Alfred P. Sloan. Sloan took over General Motors in 1922. He went on to build it up into one of the greatest manufacturing enterprises of the 20th century.

At the time he took it over, the company had recently gone through a series of acquisitions and mergers. The result was that the company operated as a loose federation of nearly independent chieftains.

Each of the leaders ran a unit of the company as if it were still his own company.

Sloan saw that a large integrated manufacturing business needed unity of direction and central control to be effective. But, it equally needs energy, enthusiasm, and autonomy in operations. The operating managers had to have a significant degree of freedom to do things their own way, but they had to have enough structure to function effectively together.

The leaders of General Motors before Sloan had seen the problem as one of personalities. They saw the squabbles as a series of isolated incidents: Bob needed to reconcile with Ned. Or John and Ted needed to get on the same page about developing a new product.

As a result, they ran around trying to solve all the different problems and arguments coming up between top management. Just like with the Maginot Line, they learned the lesson too specifically, focusing on the individuals rather than the broader system in which they were operating. The result was that they drove themselves crazy and the company into disarray trying to fix all these interpersonal issues.

Sloan, by contrast, saw the problem and its dynamics more generally. Sloan restructured the company in a way that could provide some decentralization to give local autonomy in operations with some central control of direction and policy. This gave the acquired companies enough autonomy to innovate, but enough centralization to be efficient and competitive. 1

Sloan, like other effective leaders, solved generic situations through a general rule and policy that can handle most events as cases under the rule.

“A country with many laws is a country of incompetent lawyers,” says an old legal proverb.

The tendency for most individuals, countries and organizations is to attempt to fall prey to the Maginot Line Problem and attempt to solve every problem as a unique phenomenon, rather than as one example of a more general problem.

The general problem which France had for many centuries was that they had a powerful and landlocked neighbor, Germany. It wasn’t like the outbreak of World War II was the first time Germany and France had butted heads.

To name just the largest outbreaks between the two powers, you had:

- The Thirty Years War (1618–1648)

- The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763)

- The Napoleonic Conquest (1805),

- Franco-Prussian War of 1870

- World War I (1914-1918).

Each of these wars was fought in a very different way and required a constant changing and updating of thinking around a more general problem as opposed to building a huge concrete wall.

An executive who has to make many decisions is both overworked and ineffectual. They are working hard but not smart. Most business executives are fully prepared to prevent the previous crisis, not the next one.

An example from the investment world is the shift we have seen following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

After the 2008 GFC, regulation was passed that meant banks had to be much more conservative with their derivatives business. Similar to the construction of the Maginot Line, this was a seemingly smart thing to do.

The use of highly leveraged derivatives in the housing market had created the largest economic crisis since the Great Depression. That is bad. No one wanted it to happen again.

However, one of the possible consequences of those regulatory changes (among many other factors, I don’t mean to imply that regulation is the only factor) is that liquidity in markets appears to be worse in times of stress like Q1 2020.

Historically, when you had big sell-offs and moves in the market, large banks would step in and make markets. Since they had big balance sheets backing them up, they could afford to take the risk at a time when smaller players would be too nervous about blowing up.

That became more difficult to do in the wake of regulatory changes.

While it’s impossible to reduce macroeconomic moves to a single factor, many of the more sophisticated investors I’ve talked with believe sharp sell-off in Q1 2020 was caused just as much if not more but the lack of liquidity than by concerns about the virus. Again, I am not reducing this down to some single factor: reality has a surprising amount of detail. It was, no doubt, a complex interaction of factors, many of which I don’t understand.

This is another incidence of The Maginot Line Problem: The lessons from 2008 were likely learned too specifically and without nuance. The lesson that was learned was something like “all leverage is bad”.

The proper lesson was probably something closer to “the current structure of the economy is tightly interlinked and with meaningful amounts of leverage which create the possibility for cascading effects across markets driven by market microstructure rather than fundamentals”.

Leverage is an important part of the picture, but only part. And, even that diagnosis is almost certainly far too simple and missing important factors!

In Praise of Snowmobiles

One reason the Maginot Line Problem happens is because it’s a lot harder to learn things generally than it is specifically. If my comments here around the appropriate course of action and mode of thinking for the French sound vague, it’s because they are!

I don’t have a sufficient understanding of German and French military history, geography, and politics to know what the French should have done, but the answer definitely wasn’t just the Maginot Line.

Knowing the appropriate course of action requires a deep understanding of the problem and looking at how all the elements can be combined to generate a new and effective synthesis.

John Boyd, who developed the OODA Loop framework, referred to this approach as snowmobiling which came from a thought experiment.

Imagine a motorboat towing a skier behind it, a tank, and a bicycle. If you break them down into the constituent parts, you have:

- a motorboat with a hull, outboard motor, and a set of skis being towed behind it;

- a tank with treads, a gun, and armor; and

- a bicycle with wheels, handlebars, and gears.

You can rebuild these constituent parts into many different incoherent wholes, but a coherent and useful whole would be a snowmobile — treads from the tank, an outboard motor and skis from the boat, and handlebars from the bike.

Snowmobiling, Boyd’s term, is how creativity really happens. It is destructive deduction combined with creative synthesis.

The Germans did this successfully: they looked at tanks, armored personnel carriers, the radio and reconnaissance planes and came up with a new and creative strategy for utilizing them. The French did not.

Many managers, executives, and investors make the same mistake: they look at things too narrowly, failing to see a broader pattern. One of my gripes about many self-help books and gurus is that they tend to focus on being hyper “actionable”. Though there is certainly something to be said for this and not getting too lost in abstractions, it can become counterproductive.

You cannot run a business or build an investment strategy by just chasing around the most recent actionable hack. You have to develop some more general conceptual understanding of what the broader system dynamics are and how to manage them.

When done well, actionable things can get people started on that path, but at a certain point, you have to step up a level of abstraction and see the broader picture.

How to do this? Well, I don’t have any actionable hacks if that’s what you’re wondering, but I can share my own experience. What seems to help me overcome the Maginot Line Problem and make better snowmobiles:

- Reading and learning a lot about a subject as well as related subjects which I can draw lessons from.

- Talking with other people that are knowledgeable about it

- Writing about it as a forcing function for clarifying my own understanding

- Setting aside time to do regular weekly reviews and quarterly reviews.

The Maginot Line ultimately proved to be a costly mistake. The French were swiftly defeated by the Germans, embroiling the world in a war even worse than World War I.

Indeed, the ultimate conquest of Nazi Germany was, in large part, due to the Allied commanders learning and using the same Blitzkrieg tactics which the German forces had used in the French invasion.

One can hardly sum up the essence of Blitzkrieg better than this line from American commander Gen George S. Patton, Jr. uttered as his forces regained the European continent.

I don’t want to get any messages saying, “I am holding my position.” We are not holding a Goddamned thing. Let the Germans do that. We are advancing constantly and we are not interested in holding onto anything, except the enemy’s ass.”

The only thing we can know for sure about the present is that it is not like the past. Charting a course forward then always requires a step into the unknown and a dance with uncertainty.

Last Updated on June 6, 2025 by Taylor Pearson