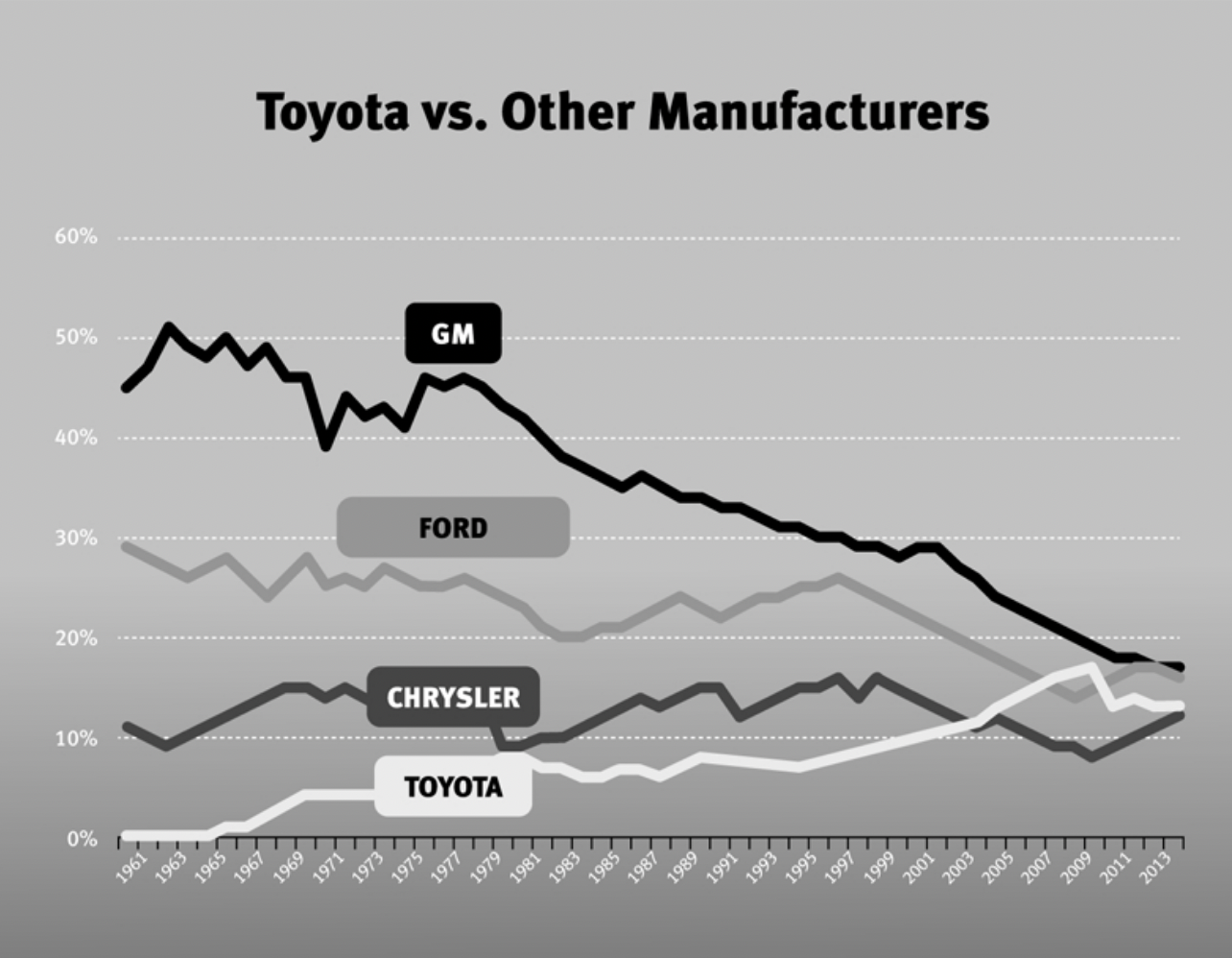

One of the most impressive business achievements of the late 20th century was the ascendance of Toyota from non-existent in the 1960s to the dominant car company in the United States.

What is particularly impressive about Toyota is that they were not in a new or emerging category. The success of a Facebook or a Google is impressive in its own way, but they were part of new categories with no established competition.

GM was founded in 1908 and represented ~50% of market share in the U.S. car market at their peak. Ford represented nearly 30%. These were established companies with decades of head starts and huge economies of scale. It’s hard to overstate how laughable the idea of a Japanese car maker dominating the U.S. market was in the 1960s.

They did not win through outspending the incumbents on marketing or even coming up with some clever new product. They won through operations and what came to be called the Toyota Production System. They won through a relentless and deeply culturally embedded focus on kaizen, continuous operational improvements.

In my decade plus of experience working with small businesses and startups, I have come to the conclusion that many business problems are actually operational problems at their core.

To take one example, When the email marketing program isn’t working, usually the correct questions to ask are:

- How are they communicating?

- What project management are they using?

- Do they have a well structured KPI dashboard to see the value of the emails?

- What is their shared mental model for how they work together?

Most things in most businesses are actually quite simple when looked at individually. It's the coordination of many simple individual tasks over time that is required to generate real, durable value. This is the realm of operations.

And yet, Operations is something of the redheaded stepchild in business. Sales and marketing is sexy. Finance touches the money. Product gets to do the big reveals. Operations are the glue that makes all these things work together, an undulating amoeba that fits all the other pieces of a business together.

I started my career in marketing, but to the extent that I am good at marketing, it is mostly that I am consistent in operationalizing the basics and doing them consistently rather than any particular marketing genius.

Though it is not sexy, operations can be a massive competitive advantage. Amazon and Toyota, two of the greatest business successes of the last 50 years are both fundamentally operationally focused companies and that focus is what has let them succeed.

I’ve spent a lot of time studying this and here are my favorite books and resources (if you have anything you would add, I like recommendations! DM me on Twitter)

Personal Operations

Managing Oneself and The Effective Executive

-By Peter Drucker

Peter Drucker is an absolute Titan of personal operational thinking and not without merit. He managed to write not one, but two of the best books on personal effectiveness ever published.

The books contain timeless wisdom that I still use every day such as:

- Tracking and optimizing where you spend your time

- Why to focus on strengths rather than weakness

- How to Prioritize

Getting Things Done

-By David Allen

The OG of personal operations, David Allen’s Getting Things Done (abbreviated GTD) is the first book that I recommend to recent college graduates entering the workforce. I read it a few months after I graduated college and everyone I have ever hired has read the book. It is, as you might expect, about how to get things done.

The premise of GTD is that most people use their brains in the wrong way. Humans are good at creative synthesis, they are bad at remembering little details. Allen argues that people waste their mental energy trying to remember details (send this report to Carol, pick up milk on the way home, etc.)

Instead, people need to use an external tool (e.g. a To-do app, note-taking apps, etc.) to ‘capture’ thoughts and have a regular review time to process and assign them. When you have a system that you trust will remind you to do the things you need to do when you need to do them, two things happen.

One, you become far more reliable and valuable to the people you are working with. Two, you have more brain space to work on important problems rather than managing minutia.

Perhaps most importantly, reading and implementing GTD makes it obvious how much of a difference good operations in your personal life can make and often inspires people to go further.

Building a Second Brain: A Proven Method to Organize Your Digital Life and Unlock Your Creative Potential

-By Tiago Forte

Building on the work of David Allen, Tiago Forte developed his Building a Second Brain (BASB) method for how people could better structure and make use of their studying and knowledge. At the heart of BASB is the PARA system, an acronym for

- Projects

- Areas

- Resources

- Archive

PARA has been a very helpful addition to GTD for me as it provides more structure and is a useful framework for working with others whereas GTD is primarily focused on working as an individual.

The BASB system comes from an important operational philosophy that looks at how you can take the work you are already doing and get the most out of it. Taking notes on something? How can you structure that to most effectively convert that into a deliverable at work? Improvements in workflow like this have massive downstream ramifications.

The Checklist Manifesto

-By Atul Gawande

Checklists work. However, it’s generally misunderstood as to why they work. I think the general perception of checklists is that they are for ‘dumb’ people who can’t figure things out on their own. As Gawande shows, this is precisely wrong. Looking in particular at studies of physicians, Gawande shows how the use of checklists can substantially improve health outcomes after surgeries. The preparation for many surgeries involves a long list of dozens of steps that need to be done in a specific order to be effective.

If the doctor washes his hands but then touches something that hasn’t been cleaned, they have re-infected their hands. It turns out that even doctors aren’t very good at remembering these details.

There are lots of roles and tasks which are similar to surgery preparation in that none of the steps are particularly difficult but they must all be done and they must be done in the right order. Using written checklists makes this work way better. As David Allen put it, it also frees up our mental RAM to focus on more important things than trying to remember a detailed checklist.

Operations Philosophy

Systemantics (AKA The Systems Bible) (My Summary)

-By John Gall

In a complex system, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. If you take the heart out of a horse and then replace it a few hours later, it doesn’t start working again like a bike. This does not mean we can’t understand complex systems, only that they play by a different rulebook.

The Systems Bible attempts (and largely succeeds) at capturing this phenomenon with quotes like:

“A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over with a working simple system.”

And

SYSTEMS TEND TO MALFUNCTION CONSPICUOUSLY JUST AFTER THEIR GREATEST TRIUMPH:

Toynbee explains this effect by pointing out the strong tendency to apply a previously-successful strategy to the new challenge:

THE ARMY IS NOW FULLY PREPARED TO FIGHT THE PREVIOUS WAR

For brevity, we shall in future refer to this Axiom as Fully Prepared for the Past (F.P.F.P.)”

Systemantics manages to make thinking about systems not just interesting but also fun. And when it comes to dealing with complex systems, a sense of humor is not a luxury, but a survival necessity…

The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics (My Summary)

-By Eric D. Beinhocker

One particularly important complex system we all deal with is the economy. The massive network of firms, people, and resources required to sustain modern life is one of the most amazing complex systems to ever come into existence.

However, most studies of the economy tend to fail to appreciate its complex and emergent nature. Beinhocker’s The Origin of Wealth is a valuable contribution to changing that which lays out the development of complexity economics over the last few decades.

Though not specifically about operations, it contains mental models for thinking about how business works. In particular, it emphasizes organic metaphors over mechanical ones. Seeing a business, not as a machine that needs a master planner, but a garden that needs a thoughtful but less domineering groundskeeper.

Seeing Like a State (My Summary/Analysis)

-By James C. Scott

Why do so many well-intentioned plans for improving the human condition go tragically awry?

From collectivization in Russia to Le Corbusier’s urban planning theory realized in Brasilia, to the Great Leap Forward in China, the last century is full of grand utopian schemes that have inadvertently brought death and disruption to millions.

Scott, a Yale professor who studies early agricultural societies, shows that even when a benevolent and well-intentioned planner meddles in a complex system, they can wreak absolute havoc.

The basic recipe for what Scott calls high modernist planning (and the failure case) is something like this:

- Someone with authority and power looks at a complex reality.

- They don’t understand how it works because it’s illegible, hard to understand from the outside looking in.

- Rather than looking for other factors that might have caused illegibility, they attribute that failure to you/the system being “irrational.”

- They come up with an idealized map of what it should look like in theory and claimed that it is superior and rational.

- They use their power to impose that idealized map on the actual territory

- They fail miserably and blame it on someone else –– usually the system they were trying to fix.

Nation-states are where this phenomenon started but it’s pretty ubiquitous at this point. If you’ve ever worked in a large corporation, you’ve seen it happen.

A new consultant/boss looks at some complex activity, say how a department is organized. It doesn’t make rational sense to them. They redesign an idealized version of what it should look like. They force everyone to work in the way they’ve designed. Everyone’s productivity plummets and they blame it on someone else.

Understanding this failure mode is essential for thinking about how to construct generative and truly effective organizations.

Images of Organization

-By Gareth Morgan

An incredibly valuable summary of the research on organizational structure, metaphors, and management.

The book is based on the idea that all theories of organization and management are based on implicit images or metaphors that stretch our imagination in a way that can create powerful insights, but at the risk of distortion. I think this is profoundly true and George Lakoff’s research in Metaphors We Live By would strongly agree.

The book covers 8 different metaphors for thinking about an organization. The first, and by far the most common in my experience, is the mechanical metaphor. Classical “scientific” management theory tended to view companies like the production lines on their factory floors and workers as the machines.

There is a certain usefulness to this metaphor but it leaves massive room for improvement and understanding. Morgan goes on to look at alternative metaphors including:

- Organizations as Organisms

- Organizations as Brains

- Organizations as Cultures

- Organizations as Political Systems

- Organizations as Psychic Prisons

- Organizations as Complex Systems

- Organizations as Instruments of Domination

Each of these metaphors is both useful and limiting in its own way and a better understanding of each allows for a more thoughtful shaping of an operational climate.

The Toyota Production System (My Summary)

-By Taiichi Ohno

I titled my summary of The Toyota Production System “The Toyota Production System: A Love Letter” so I think it’s clear where I stand on Toyota.

Having read many crappy operations books, discovering the history of Toyota was like finding water in the desert. These people really got it at a deep and fundamental level, not in a business-book-consultant-bullshit level.

The Toyota Production System began through the observation of how a supermarket works.

Supermarkets must make certain that customers can buy what they need at any time. If you run a supermarket and 10% of your products are always out of stock, customers will stop coming.

They won’t be able to get everything they need when they need it and will need to go to another store to complete their shopping. Why wouldn’t they just go to the other store to begin with at that point?

In a well-run supermarket, labor is not wasted carrying items that may not sell. Customer purchasing is carefully monitored and replacement goods are stocked on the shelves and ordered just as they are needed.

This sounds basic, and I guess it is, but it’s also what pretty much every business needs to do: give their customers what they want, when they want it.

The process which makes this works for a supermarket is elegant in its simplicity and effectiveness:

The customer goes to the earlier “process” (the supermarket) to acquire the required parts (groceries/commodities) at the time and in the quantity needed. The customer’s purchase triggers an earlier process which produces the quantity just taken (restocking the shelves).

If we want to go farther back down the chain, we can also see that the re-stocking of shelves triggers additional purchase orders (an earlier process) and the additional purchase orders trigger the production of those goods and the restocking of whatever inputs go into their manufacture and so on down the line.

This core model is where Toyota’s philosophy started, though the ways in which one achieves that go far beyond. Though most of Ohno’s writing focuses on manufacturing businesses, the principles including just-in-time, jidoka, kaizen, and genchi genbutsu are broadly applicable to any type of business.

The history of Toyota and their rise to prominence is about all the evidence one needs for its effectiveness.

The Timeless Way of Building

-By Christopher Alexander

Taken at face value, this is a book about a theory of architecture. At another level, it is a beautiful treatise on how we can think about our built environment – cities, buildings, and rooms in a more complex and nuanced way. And, at yet another level, it is a theory about how complex systems – be they businesses or cities – should be thought about and developed in order to make them robust and beautiful.

Author Christopher Alexander believed that modern architecture became bankrupt and laid down his own theory as to how it could be rebuilt.

I think that modern management theory is bankrupt in much the same way that modern architecture is and there are many parallels one can take out of this book.

The Goal

-By Eli Goldratt

Originally published in 1984, The Goal is a business parable classic that has helped generations of managers and business leaders understand how to structure and prioritize their businesses.

In The Goal, Goldratt lays out his Theory of Constraints, showing that at any given time, a business or department has a single bottleneck that is holding back all its operations.

While the inclination for many leaders is to focus on improving ALL the aspects of the business, it’s a laser focus on solving problems at the bottleneck that leads to growth and results.

Goldratt shows his methodology for systematically identifying and removing bottlenecks in a business.

See my version for small business: The Business Production Function: A Framework for Growing Early Stage Ventures.

The 80/20 Principle

-By Richard Koch

The 80/20 rule states that in a complex system, roughly 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. It was initially developed by economist Vilfredo Pareto who noted that approximately 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population.

The 80/20 rule is a helpful rule of thumb for thinking about power law distributions, a central feature of complex systems.

In The 80/20 Principle, Koch shows how business people can use the 80/20 rule to get more done with less effort, eliminate wasteful activities, and sell more to their best customers.

The OODA Loop and All Things John Boyd

OODA is an acronym that stands for:

- Observe

- Orient

- Decide

- Act

It was developed by John Boyd who began his career as a fighter pilot. In the late 1950’s, Boyd was the best fighter pilot in America and possibly the world. He was called “Forty-Second Boyd” because he could defeat any opponent in simulated air-to-air combat in less than forty seconds.

He was more than just a great stick-and-rudder man, though; he was a strategist. He had developed Energy Maneuverability (E-M) Theory in his spare time in the 60’s. E-M Theory would revolutionize the way air-to-air combat was taught and fighter planes were designed around the world. It is still the basic philosophy that fighter pilots around the world base their decisions 60 years later.

The OODA loop was Boyd’s generalization of Energy Maneuverability Theory. It is often seen as a decision-making model but can be more accurately described as a model of individual and organizational learning and adaptation.

Boyd was notorious for not writing things down but some good resources inspired by Boyd or Boyd adjacent include:

Tempo (my summary)

-By Venkatesh Rao

Tempo is a look at decision-making that focuses on narrative as opposed to a more traditional “calculative rationality” that you see in most decision-making research. Rather than focusing on how to be more “rational,” it acknowledges and embraces the idea that humans are not dispassionate calculators.

Rather, we rely heavily on narrative and story to make decisions about a world that is so complex we could not possibly engage in rational calculation even if we wanted to. Starting from this premise, it looks at how we can embrace and improve our ‘irrational’ decision-making.

Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War

-By Robert Coram

An excellent biography of Boyd that gives context to his thinking.

Certain to Win (my summary)

-By Chet Richards

How does one company outcompete others to succeed in the marketplace?

I think the somewhat abstract nature of this framing is important. Most business books tend to start off much more tactically, at a lower level of abstraction: how to build an audience, how to build a million-dollar sales funnel, or how to hire someone.

These are useful and important skills to winning at business but without a proper strategic framework within which to function, they are, at best, less effective than they could be. At worst, they are counterproductive.

Chet Richard’s Certain to Win is a book that seeks to look at the broader strategic question. Instead of offering cliches or various tactics that sound great but lack a coherent framework for making them effective, it appropriately sees business as a complex system and helps to build a framework for operating effectively in it.

Chet Richards worked with John Boyd, most well-known for his creation of the OODA Loop. In Certain to Win, Richards takes the lessons Boyd applied to modern warfare and seeks to apply them to business. It is a frame of reference which is still broadly under-appreciated.

There are three core principles in Certain to Win that I believe every business would benefit from understanding and implementing.

- Effective Orientation via “Fast Transients” and “Snowmobiling”.

- The pre-eminence of Vision and Culture.

- The Farthest Down the Chain Principle.

Science, Strategy and War

-By Franz P. Osinga

This one gets pretty wonky and is also one of my favorites on this list. It was a PhD thesis for a Dutch military professional that goes through, in detail, all of Boyd’s published worked and unpacks the thinking and context behind them.

By offering a comprehensive overview of Boyd’s work, this volume demonstrates that the common interpretation of the meaning of Boyd’s OODA loop concept is incomplete. It also shows that Boyd’s work is much more comprehensive, richer and deeper than is generally thought.

Business Operations (Tactical)

Work the System

-By Sam Carpenter

Work the System was probably the book that originally got me interested in business operations. I read it the first year I was at my first job and it instantly made sense to me. The company I was working for at the time had a bunch of smart people, but relatively little organizational structure. After finishing it, I immediately went on a tear making Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and the business was transformed with in a year.

Work the System is the story of taking a business in a similar place and transforming it into a highly efficient operation.

“My overall life role is as a project engineer: that is, someone who accepts a problem, designs a mechanical solution, and then makes that solution work in the real world. I’m a project engineer in every aspect of my life including the personal roles of father, son, brother, husband, and friend.”

Sam Carpenter put in words something I’ve always found true – systems liberate. Much to the chagrin of many creatives and entrepreneurs, it is in fact the development of defined processes and systems which enable freedom, creativity and profits.

This is a must-read for anyone who feels “stuck” in their business and unable to get out of day-to-day operations.

Sam explains how he used systems to increase profits, the quality of his team all while decreasing his time investment in the business.

Where Work the System (and almost all other business books on operations) come up short is an over reliance on a mechanical metaphor for thinking about how to run a company. So it’s a very good starting point and generally the first book I send people who have no operational structure, but it can become limiting. It pairs well with operational philosophy books above which encourage alternative methods of thinking about business.

High Output Management

-By Andrew S. Grove

A well-deserved classic of the management genre from one of the great business managers of the 20th century. Andy Grove stewarded Intel through one of the biggest and most successful business pivots in history and this is his philosophy on management.

There are lots of actionable and useful pieces in here like how to do performance reviews, run meetings, and draw reporting lines.

Best Practices for Operational Excellence (My Summary)

-By Luca Dellanna

A more recent entry that I think better incorporates some of the more organic metaphors other business books miss out on.

The book starts with 4 Operational Principles:

- Good managers set unambiguous, individual and rewardable objectives.

- Good managers always explicitly assign full accountability together with objectives.

- Good managers demonstrate priorities with visible costly actions.

- Good managers are obsessively consistent in holding their subordinates accountable.

These are well explained with examples before the second half of the book gets more tactical and lays out specific suggestions such as Management Walks, Weekly Meeting Agendas, and how to create Standard Operating Principles.

My favorite insight from the book was from the 3rd Principle: Good managers demonstrate priorities with visible costly actions.

Said another way, Company culture builds around whatever is signaled in a costly manner.

The Great CEO Within

-By Matt Mochary

This book is hyper-tactical in a good way. It is basically a set of best practices or SOPs from a coach/consultant that worked with many of the most successful Bay area startups of the 2010s including companies like Coinbase, Plaid and Flexport.

I found that the suggestions for problems I had dealt with before all rang true which gave me quite a bit of confidence that the other advice was equally good.

The book starts with important individual habits for founders and goes on to group habits and processes to be applied across the whole business. I think pretty much everyone will pick up some ideas in here for where they could improve immediately.

Management

-By Peter F. Drucker

I mentioned that Peter Drucker managed to write two of the best books on personal effectiveness, well, he also wrote one of the best books on management as well. Drucker basically founded the entire field of management as an area of serious study and somehow managed to remain relevant for decades that followed.

Management is his set of best practices that is basically a summary of his life’s work and goes into company structure, decision-making, communication, and strategy.

Business Case Studies

All Things Toyota

The Toyota Way

-By Jeffrey Liker

Obviously, I have made my feelings for Toyota clear at this point. Though many misunderstand Toyota, this book by Jeffrey Liker gets it. He decomposes Toyota’s philosophy down into some core operational principles while remaining cognizant of the fact that any notion of a “recipe book” which merely tells people how to copy Toyota completely misses the point.

The book dives into the core of Toyota’s operational philosophy while providing lots of good examples and decomposing them into helpful principles.

The Sayings of Shigeo Shingo

-By Shigeo Shingo

Along with Taichi Ohno and others, Shigeo Shingo was one of the great minds behind the Toyota Production System.

The Sayings of Shigeo Shingo leads you through Shingo’s thinking. It shows how, in many cases, the most brilliant ideas are often so simple they’re overlooked.

All things Amazon

Alongside Toyota, I will read just about anything on Amazon that I can get my hands on. Though much has been written. Some of my favorites are:

The Everything Store

-By Brad Stone

This is the narrative nonfiction account of Amazon’s founding and ascendancy to tech giant. It chronicles the early decisions and cultures that led Amazon to where it is and gives a sense into what the day-to-day priorities look like for such an effective company.

Working Backwards

– By Colin Bryar & Bill Carr

Working Backwards is an insider’s breakdown of Amazon’s approach to culture, leadership, and best practices from two long-time Amazon executives. They offer practical steps for applying it at your own company―no matter the size.

What is Amazon?

An essay analyzing what Amazon really is and how it thinks about it’s own business.

Stratechery Posts on Company Structure

Ben Thompson of Stratechery is one of my favorite business analysts and he writes intelligently on the impacts of company structure on eventual outcomes. This collection of articles looks at different companies and how their organizational structure ultimately affects their business.